By Ian F. MacInnes, Alexa Sand, and Lisandra Estevez

Curating exhibitions is genuine research work that allows students to work collaboratively, engage the community, and practice public humanities scholarship. Exhibitions can teach students the fundamentals of research in a discipline while focusing on small and achievable outcomes, like bibliographic descriptions and short interpretive explanations. Exhibitions can help students understand and articulate the value of the public humanities. They allow students to practice making a persuasive visual and textual argument for a general audience. And finally, working on an exhibition is inherently collaborative, a model of humanities scholarship that is becoming more prevalent. Planning and mounting exhibitions can be resource and time intensive, but students tend to embrace the challenge. The public venue inspires them to do their best work.

An exhibition itself may be real or virtual, though whenever possible your students should have access to the actual objects they will be curating. Here are some things to be aware of if you are considering adding an exhibition project to your class.

Be open to different sources of material

The material for your exhibition is an opportunity to think creatively about the collaborative work you envision. Libraries and museums are obvious sources (and venues), but so are local historical societies. Smaller museums and libraries often have interesting collections of uncurated material, giving students an even more meaningful experience. Libraries also often have unadvertised collections of objects that can supplement documents. If local archives don’t have what you need, it is sometimes surprisingly easy to collect items yourself. Major auction sites, like eBay, are inexpensive sources of fragmentary material. Roman glass, Greek pottery sherds, pages from early print sources, and modern ephemera are all probably within reach of your budget. Finally, don’t forget that students can create facsimiles and replicas to build out an exhibition, either working on their own or with the help of experts on campus.

Prepare the ground with your collaborators

Whether working with a departmental or college gallery space, a campus museum, your library, or another on- or off-campus venue, start discussions long in advance of the first class meeting. Think about scheduling: when will the exhibition be installed or beta-tested? When will it open and will there be an associated event? When will it close and who will be responsible for taking it down and cleaning up? Are there special considerations to be taken into account in handling materials or working in the space, or the digital environment? Who will be responsible for what aspects of student support? For example, if display “furniture” such as supports or hanging hardware need to be constructed or installed, will the students do this, or will it be delegated to a preparator, and if so, is the service gratis, or fee based?

It’s a good idea to have all of this worked out ahead of time. That way, you can give student curators a comprehensive “map” of what their responsibilities will be, and what support they can expect from staff or curators employed by the exhibition venue.

Scaffold the needed skills into the class material

Exhibitions are daunting assignments from a student’s perspective, so it’s extra important to build student skills slowly from a base. Scaffolding, along with clear benchmarks, gives students a better sense of direction of where to start with this project. It is especially important in working with students who might have little experience with research in our disciplines.

Some early steps include

- Exhibition title;

- Proposing works to include;

- International Standard Bibliographic Description of items; and

- Annotated bibliographies.

More complex later steps include

- Interpretive descriptions;

- Transcription and translation;

- Introductory explanation for the entire exhibition;

- An exhibition catalog;

- Posters advertising exhibition; and

- Oral script of presentations for exhibition opening.

While scaffolding undergraduate research assignments might seem time-consuming, it actually allows for better time management for both students and instructors. By providing clear goals from the start, students get ongoing feedback regarding the progress of their project. Scaffolding also helps to model the research process for students step-by-step. They begin with a question, transform it into a statement or thesis, and carry out research for a bibliography. They then produce a substantial, thoughtful project that can be shared with the academic community.

Remember you are part of the team

As instructor, you are responsible for evaluating and assessing student work associated with the exhibition, but don’t forget that your name will also be publicly associated with the results. This means that you should consider yourself part of the team as well as an outside judge. While you normally avoid editing students’ work for excellent pedagogical reasons, you should not be shy about revising material that will be made public. Doing so not only helps create a better outcome but lets your students know that you are willing to work alongside them on a successful event.

Know your tools

Mounting an exhibition, whether actual or virtual, requires technical skills. As for most pedagogy, don’t evaluate your students on skills you don’t have yourself, including digital skills. And try to stick with exhibitions you feel confident about mounting yourself if you had to. Having a committed collaborator is often helpful, but don’t expect your IT department or your archivist to fill in for skills you lack.

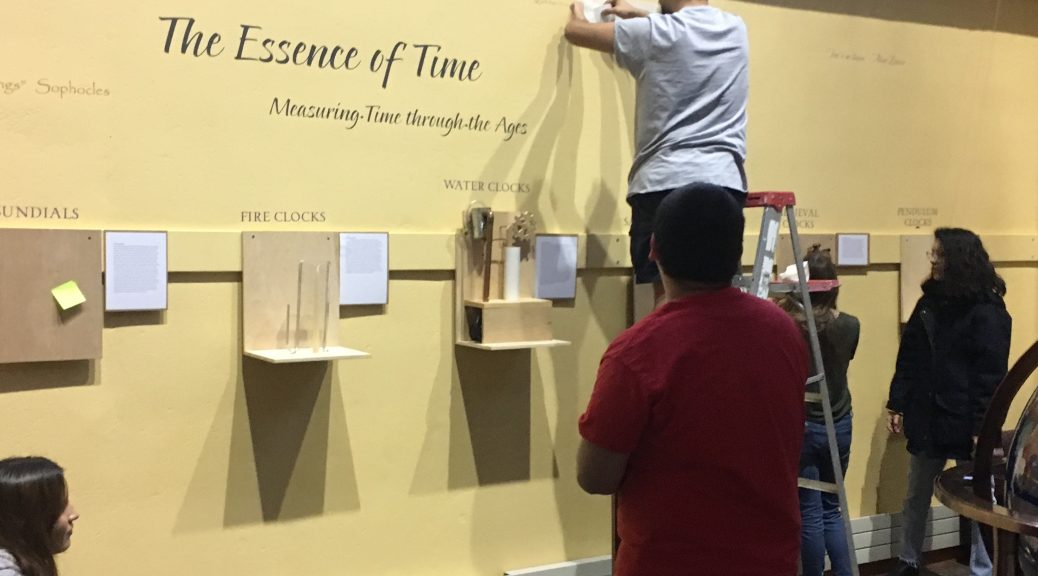

Leave time for installation

It is tempting to think that final installation will go quickly since it’s just a physical event. But installations, whether physical or digital, take time, care, and can run into obstacles that may require time to fix. If you expect students to include replicas, make sure you plan for the time, space, materials, and expertise to help them achieve these goals. When possible, set aside some class time for installation. It’s practically the only time you can actually require all students to be present.

Plan your publicity

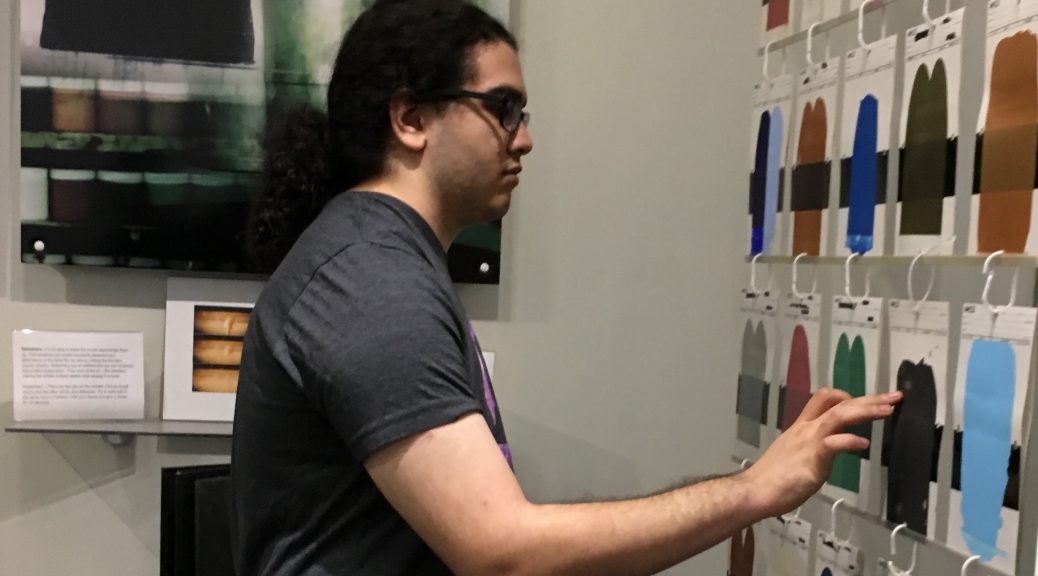

The more public your exhibition, the more your students will be inspired to do their best. Make publicity part of the project. Consider setting aside time and money for a “grand opening” event that includes campus stakeholders and influencers. As Chip and Dan Heath reveal in The Power of Moments, celebratory milestones can give students a sense of achievement and closure. And dissemination is a key element of undergraduate research: students should have the opportunity to interact with public visitors to their exhibition.

Further reading

Several models for curatorial work are discussed in this CUR Quarterly essay by Alexa Sand, Becky Thoms, Darcy Pumphrey, Erin Davis, and Joyce Kinkead of Utah State University, where the university’s library and art museum have often been the venues for student curatorial projects, and where the expertise of the library and museum staff are a critical factor.

Furthermore, a couple of great resources for composing museum labels and texts and creating inclusive exhibitions can be found here.

A comprehensive source for labels:

Serrell, Beverly. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach. Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Didactics:

Writing Text and Labels (Australian Museum)

The V&A Ten Point Guide to Gallery Text

Quick Guide to Adult Audience Interpretive Materials (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Cognitive underpinnings:

Heath, Chip and Dan, The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact . Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Check out our other best-practice guides for faculty:

- Teaching paleography and manuscript transcription

- Organizing a poster session

- Assessing scholarship and creative inquiry – examples