Transcription of early material isn’t just a mechanical process. Rather, teaching paleography introduces students to complex problems shaped and solved by language. Understanding a difficult text requires attention to detail and and wide-ranging research. Depending on the nature of the documents, students must draw on areas such as lexicography, cultural history, ethno-pharmacology, mathematics, theology, basic Latin, and chemistry. Transcription also helps students open up the canon to new voices, particularly those of early women writers whose work less often found its way to publication and who worked in genres not traditionally acknowledged as literary or scientific.

In the last ten years, major archives have made thousands of multi-page manuscripts available in high quality images. Some examples for English manuscripts include the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Library of Congress, the Wellcome Library, the British Library, and the London Metropolitan Archive. You may already be aware of materials in your area of expertise, but it not, be sure that there is fresh material out there to be discovered!

If you want to bring this powerful method of undergraduate scholarship into the classroom, you’ll first need to work on teaching paleography and then look for collaborative transcription opportunities (so students’ work can be disseminated). Here are some guiding principles.

Teaching Paleography

1. The best course is the one you create yourself

While there are a few examples of teaching paleography online, the best solution is always the one that you develop yourself because it will best fit your course content and outcomes. If you want students to work on letters, for example, then learning the conventions in wills is beside the point. Choosing your own samples allows you to help students learn the conventions and language of the texts they will have to transcribe. It also lets you bring in samples that are directly relevant to the content you are teaching on a given day. Last, it lets you control the level of difficulty students encounter.

2. Slow and steady

Consider working paleography in slowly over time instead of creating a “unit” in the topic. While an intensive week-long workshop might be fine for faculty members who are already expert in an area of study, undergraduates need time and practice to develop their skills. Their growing expertise in your subject matter itself will help them learn paleography. Try working on a few lines from a different manuscript every day.

3. Embrace your own ignorance

If you don’t consider yourself an expert in paleography, don’t worry. As long as you are ahead of students, making your own effort visible will promote what is often called a “growth mindset”: paleographic skills are a result of effort, not intelligence. In addition, calling attention to your own process is a way of showing students an expert in the field working at the edge of his or her own expertise, a rare opportunity.

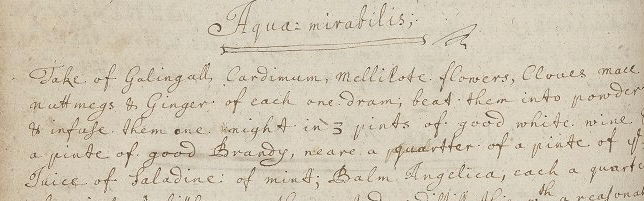

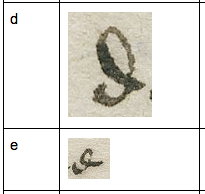

4. Have students create analytical alphabets

Transcription helps students develop a detailed and analytical approach to language. To encourage this, and to help them with their transcribing, consider asking them to create alphabets for a given hand, with screenshots attached to letters (most students are comfortable with the technical requirements).

Transcription helps students develop a detailed and analytical approach to language. To encourage this, and to help them with their transcribing, consider asking them to create alphabets for a given hand, with screenshots attached to letters (most students are comfortable with the technical requirements).

5. Teach the tools

Deciphering difficult manuscripts is a lot easier if students are familiar with external tools. For English Paleography that includes the Oxford English Dictionary, digital archives of printed texts, like Early English Books Online (EEBO), Wikipedia, online maps, and sometimes even Google’s auto-complete feature.

5. Emphasize collaboration

The transcription of manuscripts for public presentation is a collaborative process, so it’s important to emphasize collaboration from the beginning by having students work in groups, share problems, and cooperate on finding solutions.

Collaborative Transcription

1. Join a collective task

There are several ways to make sure that students find a way to disseminate their work. If you’re not too worried about feedback, Zooniverse offers several options from “Shakespeare’s World” to the transcription of 19th-century ship logs, or World War I diaries in projects like “Operation War Diary” or “Measuring the Anzacs.” If you want your students to be more deeply involved in a project, there are online collectives devoted to coordinating transcription. For example, the Early Modern Recipes Online Collective (EMROC) welcomes undergraduate participation and even sponsors a public biannual “transcribathon” focused on a single long manuscript. Other options include Smithsonian Digital Volunteers. Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO), itself a place for transcription, offers this extended list (developed in 2013).

2. Make room for reflection

Whatever projects you choose in terms of teaching paleography, don’t forget to make room for reflective writing that gives students a chance to gain perspective on the nature of scholarship in the humanities.

Please send in any edits and suggestions for improving this page.