Interdisciplinary research projects offer innovative approaches to making work in the arts and humanities more visible. Zach Zito, a student at Utah State University, has been working hard on a project that combines physics and philosophy. His work focuses on quantum mechanics and relativity of time. We reached out to him for an interview to learn more about his research.

CURAH: What is the nature of your research?

ZZ: I have the privilege of engaging in research with Dr. Brittany Gentry (philosophy) and Dr. Charles Torre (physics). Our research centers on the role of time in physical systems. It is an interdisciplinary endeavor, drawing heavily on concepts from the relevant philosophic literature as well as modern physical theories.

From Aristotle to Newton to Einstein, great thinkers have established diverse ways of viewing the physical word based on different conceptualizations of time’s nature. In physics, one’s assumptions about the nature of time play a role in how scientific theories are structured. Interestingly, two of today’s most important disciplines within physics — relativity (which describes the cosmos) and quantum mechanics (which describes the sub-atomic) — make use of different and irreconcilable notions of time. This is puzzling because both theories make remarkably accurate predictions and are fundamental to modern technology and our understanding of the universe. How could two theories, both of which serve us so well, contradict one another? This is the question at the heart of our research.

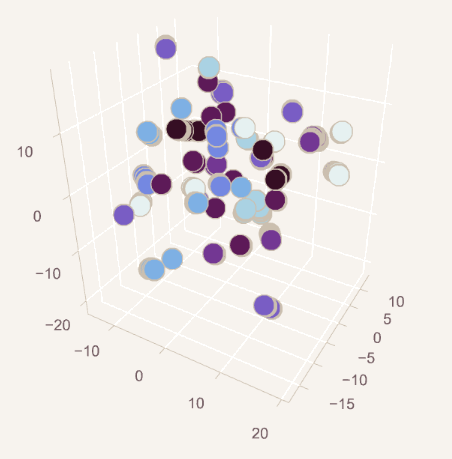

Digging into the literature, we thought hard about the metaphysical status of time: what we are truly referring to when we speak about temporarily. Inspired by the work of Barbour and Bernoulli (two prominent physicists), we set out to find a way to describe particle systems (not unlike those studied in quantum mechanics) in a manner that is in harmony with the findings of relativity. We have made some promising advances in this regard. Today, we are working on establishing canonical methods for defining a relativistic rime metric in systems that share more and more qualities with full-fledged quantum mechanical systems.

CURAH: What were the easiest and hardest things about the work you did?

ZZ: Philosophers and physicists alike have been thinking about the metaphysics of time for… quite some time. This made it relatively easy to find high quality literature related to the subject in question. We looked at several works from prominent thinkers to round-out and purify our conception of clocks, motion, and time to establish a solid basis on which to proceed. the most difficult part was synthesizing all the material, crystallizing our findings into mathematical expressions and robust metaphysical explanations to describe our models. Despite the difficulty, Dr. Torre, Dr. Gentry, and so many great thinkers before us, we were able to come to a satisfying conclusion.

CURAH: What kinds of things did you learn? (about your topic, about scholarship, or about yourself)

During this research, I had the opportunity to learn more about the existing literature on the philosophy of time and change as well as advanced methods in physics for analyzing and describing systems. Particularly, I learned about the intricate relationship between temporal succession and motion and about the importance of symmetries and conserved quantities in physics. This alone felt like a top-rate educational experience and affected the way I see the world around me and how I interact with the academic disciplines of philosophy and physics. On a deeper level, I learned how engaging serious investigation into deep questions can be. I was surprised at the high level of collaboration that took place across disciplinary, spatial, and temporal boundaries. I hope to continue to participate in this ongoing conversation, exploring the secretes that nature has in store through creative synthesis of experience, mathematical rigor, and careful consideration.”

CURAH: Did you make any discoveries along the way?

ZZ: Yes! We established a framework through which to view change, time, and matter and discovered an equation that describes simple motion in a model-universe without reference to the type of “assumed” time that relativity theory demands we abandon. Functionally, we found a way to mathematically convert a complicated combination of measurements into a clock which is internal to the system under study. We did this by examining the quantities of the systems that are conserved due to symmetries and exploiting them to craft a mathematical clock. This means that in principle, systems can be coherently understood without external reference, suggesting that a deeper understanding of the very early universe may prove accessible. As of now, we are searching for a similar result that can be applied to more complex systems involving quantum properties and more interacting particles.

CURAH: How has the project helped you in your career goals?

ZZ: This project allowed me to grow personally and learn a great deal about unique spaces in physics and philosophy and about research in general. Because my career goals include future work in both philosophy and physics research, this project has been of utmost value to me in that regard. This project has also given me a look into the details of research work in these fields, which helped give me a better sense of what exactly I’d like to focus on in my career and hence what I should be studying and investigating now in preparation.

Interested in hearing about more undergraduate students and their research? Check out our page dedicated to these profiles!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License