Sometimes undergraduates have an advantage over more senior scholars: pursuing two majors can make them more radically interdisciplinary and more open to unconventional combinations. Olivia Brock, Utah State University ’21, is a double major in mathematics/statistics and art history, interests that combined in her recent project on the astrolabe, that most beautiful tool of late medieval mathematical and astronomical thought. Olivia recently spoke with CURAH about her work.

CURAH: Tell us about your project.

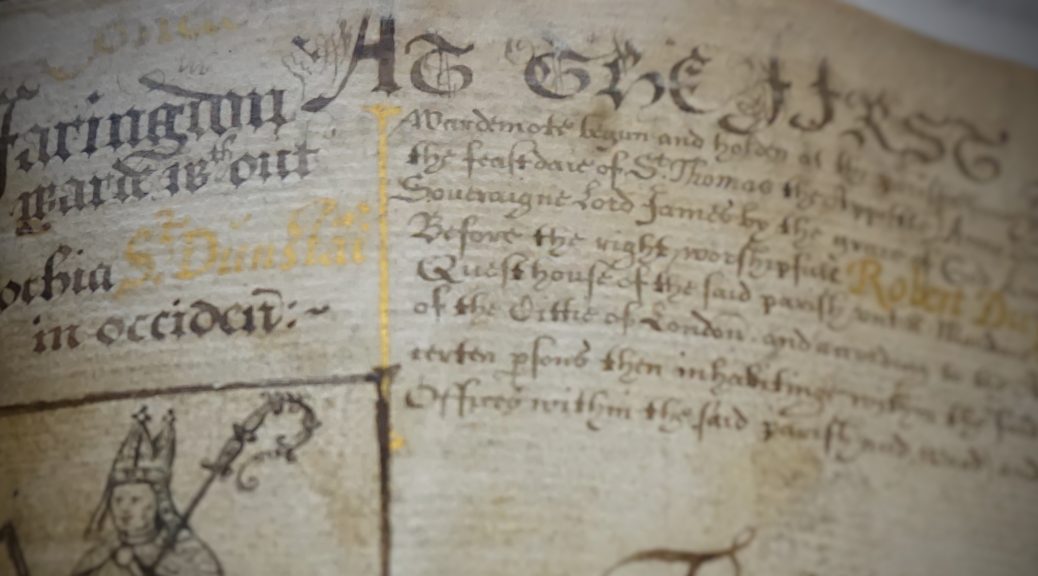

Olivia: My project is designed to answer a question: how can interdisciplinary conversations between humanities and STEM fields be facilitated through the examination of material/visual culture? In particular, I am answering this question by studying the astrolabe, a medieval scientific instrument that puts into question the historical categorization of objects. As an object that is scientific, artistic, religious (and I’ll even add pseudo-scientific), the astrolabe presents a slew of interpretive challenges. I am examining the ways historians of visual and material culture have categorized these objects, and how their categories can limit our ability to fully understand astrolabes as the unique, specific, and complex objects that they are.

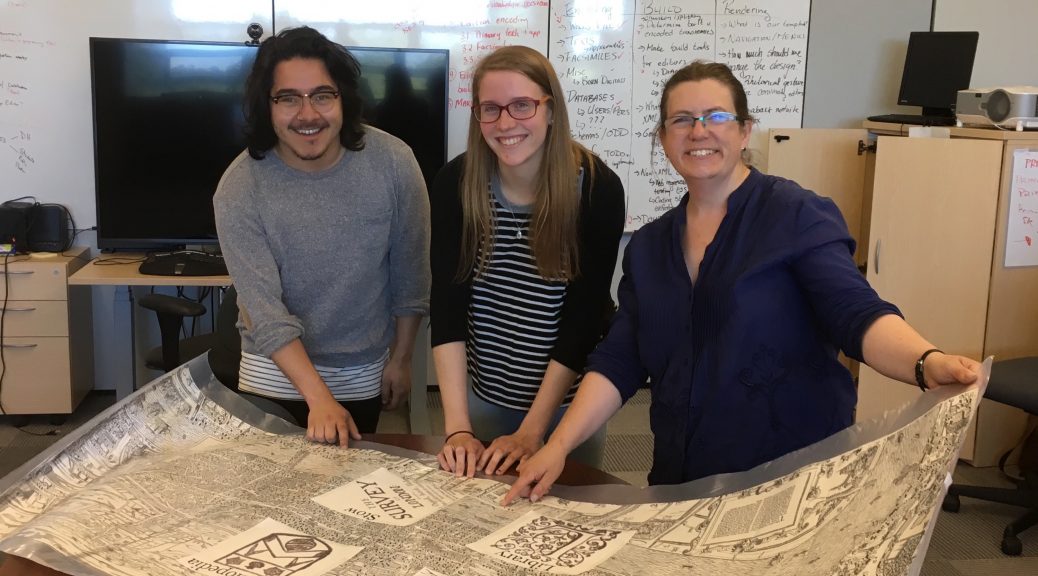

In addition, I hope to create an interdisciplinary dialogue that allows artists, scientists, scholars, and others to interact with intellectual ideas that may not be familiar. Ideally, through the dissemination of these ideas in writing and presentation, I can help the widest disciplinary audience connect with a single object and learn about new fields or ideas.

This particular goal is really important to me. As both a math/stats and art history student, I get a lot of questions about why I decided to do both majors, and comments regarding how disparate these fields are. Though these fields are quite different, and a traditional undergraduate education in either makes the bifurcation even more prominent, I have found that there are a lot of ways that these fields complement each other. It just takes a conscious effort to find these connections. This is why I’m so excited about this project: it allows me to pursue the connections I’ve found in a ways that go beyond traditional art history or math classes.

CURAH: What are the easiest and hardest things about the work you’re doing?

Olivia: There are a few bumps that I’ve run into over the course of this project that have really stood out to me. First, methodology. I work as a writing tutor in the Science Writing Center here at USU, and a big part of my job is helping students with their “Methods” sections. These are strict, orderly, pre-determined methodologies that make predicting the course of scientific research much more feasible. For me, as a scientifically-minded person, the more subjective methodological approach to my art historical research has been difficult to adapt to. I can’t create a step-by-step guide to my research as one might for a lab experiment.

The next bump I ran into was while working to develop an overall thesis for my project. How do I come up with an original and interesting claim, while at the same time ensuring that I can ground my ideas with established literature and evidence? The balance between originality and credibility has been difficult for me to maintain. Fortunately, in Dr. Alexa Sand I have a great and experienced mentor who has really helped me achieve this balance.

I’m not sure there’s been anything I’d specify as being “easy” for me. I’ve had a lot of ups and downs. But I love the work and subject matter, and that makes it easier for me to stay excited and motivated about this project.

CURAH: What kinds of things have you learned? (about astrolabes, about scholarship, or about yourself)

Olivia: I learned

- that even the most basic object can have a plethora of intangible functions and relationships that become apparent when you look at the object in a different light.

- that the astrolabe is just a single example of the arts and sciences working in tandem: there are so many interesting multidisciplinary interactions that can be found over the course of history. They just require someone to look for them.

- that scholarship is hard, but it’s worth it. The knowledge that I can take an idea and pursue it as far as it can be pursued is incredibly rewarding.

- that I may love sharing my ideas a little more than I love pursuing them. I’ve really enjoyed this process, but my favorite parts, so far, have been the times when I’ve gotten to interact with my research community and share my ideas and knowledge with other curious students.

CURAH: Have you made any discoveries along the way?

Olivia: I didn’t make anything that I would call a “discovery.” However, I never had the expectation of major discovery. My goal for the project is to pursue an idea that is personally important to me and important to the academic community at Utah State. I’m not trying to answer any major questions or problems but rather working to create discussion among my peers.

Because of this goal, however, I have helped some other students make small discoveries. Many students “discovered” the astrolabe for the very first time upon our conversations. Others may have discovered that there are a number of connections between the humanities and STEM that they may not have been aware of before. And others may have even discovered that there is a place in the research realm for even the most bizarre or disparate of interests. I also made personal discoveries about myself and my interests that will undoubtably change the course of my academic and professional career.

CURAH: How do you imagine the project will help you in your career goals?

Olivia: I must admit that my career goals are a bit unclear right now. However, through this project, I have become much more open to pursuing academic scholarship, at least through graduate school, and maybe into a career. This project also taught me that I love talking and writing about science in a non-scientific way, which has sparked ideas about potential careers in scientific communication or scientific journalism.