These days, study of the archives often begins with digital images, but an in-person visit to an actual manuscript remains a powerfully transformative scholarly experience, especially for undergraduates. Sheridon Ward, Ohio State University ’21, was lucky enough to spend time working through a massive and dense wardmote inquest book at the London Metropolitan Archives (the LMA). Sheridon has a double major in Medieval & Renaissance Studies along with Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology. CURAH caught up to her after her visit to the LMA.

CURAH: Tell us about your project.

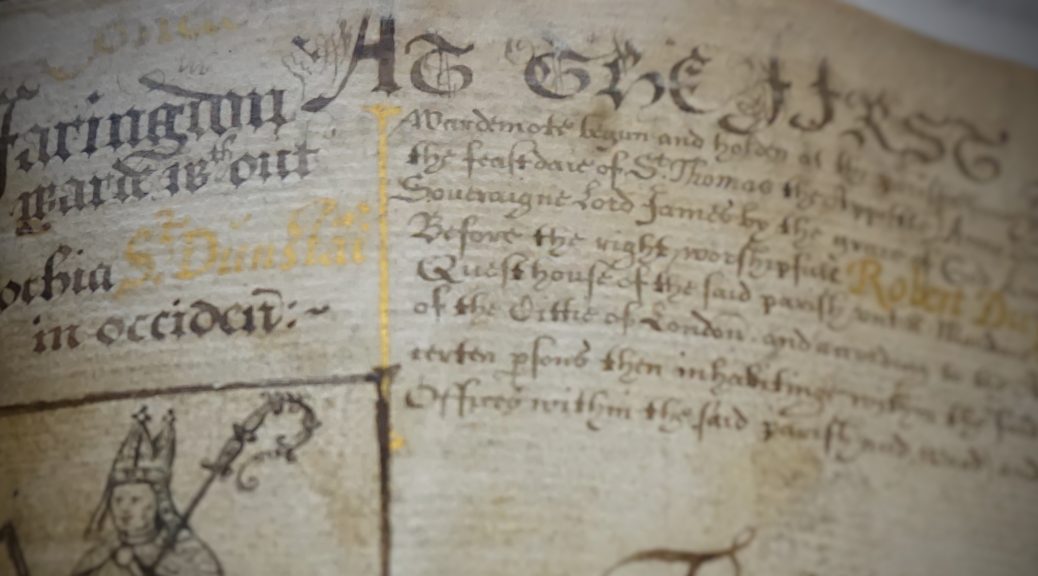

Sheridon: During the autumn semester of 2018, I took a class that explored popular culture in 16th and 17th century London with Professor Chris Highley. As the final project, we were assigned to write an article for the Map of Early Modern London (MoEML), a map based on the Agas map that was drawn around 1561 and reprinted in 1633. Professor Highley introduced me to wardmote inquest books as a possible theme-based entry for MoEML, specifically the St. Dunstan in the West inquest register. Though it started as more of a term paper than anything else, I have continued working on the project since then, and I finally got to visit the book itself when I was in Europe over the summer.

Originally, I worked using photos that Professor Highley had taken during his visit at the LMA, and I started to decipher the pages in the massive volume that spans from 1558 to 1823. I only studied pages within the early modern period in the first volume. These pages detail the sessions of the wardmote inquest for the Faringdon Without Ward. It names the inquest members, lists prominent businessmen (the licensed and unlicensed victuallers–sellers of alcohol– for example), and then “presents” people who have committed offenses to the Lord Mayor of London for redress. These offenses can range from petty complaints against poultry dealers for their baskets protruding too far into the road to accusations of adultery.

Overall, my archive project summarizes and explores the wealth of knowledge of everyday life that can be found in the pages of the wardmote inquest book. It reveals their priorities and values, how government on the smallest level worked, and how they systematically and scrupulously organized these sessions. Additionally, it addresses questions of social mobility and social standing by studying how aldermen were affected by their participation and what infractions were and weren’t punished.

CURAH: What are the easiest and hardest things about the work you’re doing?

Sheridon: The greatest obstacle that I faced during this project was unquestionably deciphering the secretary hand in the documents and coping with the fact that English spelling wasn’t yet standardized. I frequently had to use the OED Online to verify the spelling of the word that I thought I was seeing in order to link it to the modern spelling of the word.

Another obstacle was the monotony of the court proceedings. While snippets of information were fascinating to read, most of the items dealt with defective pavements or improper weights and measures. When each sentence is a struggle to decipher, it makes skimming for the more unique items much more difficult.

The easiest part of my research was finding the resources that I needed. Prof. Highley would send me frequent emails with articles related to wardmotes, and the LMA created a welcoming environment for looking at these documents. I was originally intimidated by handling a document so old, and I was terrified that they wouldn’t even let me into the archives to look at the document, but I was surprised at how painless the process was even though I’m just an undergraduate.

CURAH: What kinds of things have you learned, about the early modern period, about scholarship, or about yourself?

Sheridon: Through this project, I’ve learned a lot about early modern social structures and how they parallel our current structures and preoccupations. When I was exploring the part of London that I was studying, I came across a sign that listed the current aldermen of the Faringdon Without Ward. While some of these aldermen are now alderwomen, it was surprising to learn that these government structures still exist so similarly 400 years later.

I also learned that no matter how much passion and inspiration you have for a project in scholarship, you still need determination and discipline. Otherwise, you miss those small snippets of unique stories and information that actually breathe life into the document. And although technology has evolved to give scholars greater access to important materials, nothing compares to handling the material artifact itself. It provides a wealth of information in its own right, even before you read the words on the page.

CURAH: Have you made any discoveries along the way?

Sheridon: While I haven’t found any groundbreaking information, one thing that struck me was just how intrusive some of these documents seem. The extent to which the rest of the community is involved and watchful of everyone else seems like an invasion of privacy to my modern sensibility, but it was entirely normal then. They kept track of who came to church regularly and reported people who failed to attend church as “recusants.” However, even though this is the type of issue that would be presented to the Lord Mayor, the frequency with which some people were reported seems to suggest that it wasn’t effectively handled or simply wasn’t a priority.

Henry Lusher, for example, appears almost every year as a recusant from 1621 to 1651. However, in 1622, he was named as a petty juryman, and the fact that his recusancy continues for likely more than 30 years is puzzling and raises questions as to how important regular church attendance really was in the early modern period.

CURAH: How do you imagine this archive project will help you in your career goals?

Sheridon: Learning how to read secretary hand early on in my career is a very valuable skill to have, and I have gained experience in reading court documents that are more informal and less bogged down with technical terminology as kind of an introduction to other handwritten legal documents.