This a reminder to apply for the new Joe Trimmer travel award. Please see this earlier post for instructions.

CFP for NEH’s Arts, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation Lab

The NEH is sponsoring an Arts, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation (AEI) Lab at the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University-Purdue. Project directors Doug Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz invite proposals for papers to be written during 2019 as part of the AEI Lab and the eventual symposium in the Spring of 2020. The deadline for proposals is Feb. 28, 2019.

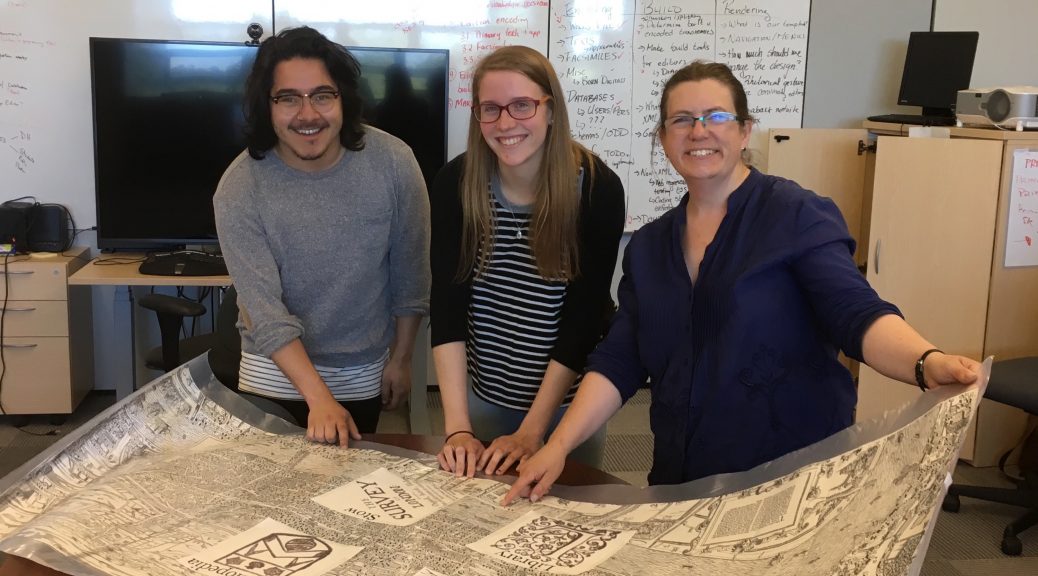

Student researchers contribute to the Map of Early Modern London (MoEML)

Large digital humanities sites can offer great opportunities for undergraduate scholarship. One model project is the University of Victoria based Map of Early Modern London (MoEML), a blend of history, geography, and literary study focused on London in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century. MoEML usually relies on advanced scholars, but through its pedagogical partnership program MoEML also invites mentored undergraduate contributions. It is perfect for contributions from undergraduates who are just beginning true humanities scholarship. And its strong peer review process and insistence on faculty mentoring mean that student contributions are always of high quality. Here two recent undergraduate scholars reflect on their work with MoEML.

Emily Allison, at Albion College, researched early London’s brothels. During the course of a summer project she wrote and encoded the entry for the Cardinal’s Hat in Southwark. Her faculty mentor was Dr. Ian F. MacInnes.

Ashton Davenport, at North Carolina State, researched Stationer’s Hall with fellow students during a recent class with Dr. Maggie Simon.

CURAH:What were the easiest and hardest things about the work you did?

Emily: The easiest thing about the work I did for the Map of Early Modern London was how immediately captivating the research was. I completed my MoEML articles with the help of a summer research grant at Albion College. That meant I was able to treat the project like a full-time job. Even logging 40+ hours a week on my research, I very rarely felt like the process was boring or tedious. Each day I was met with a renewed sense of purpose. I felt like working on the map was a puzzle that I had to assemble before the summer was over.

I found that the most frustrating thing was how my research was never complete. I would think that I had exhausted every source I could find and then stumble across a new one that would bring with it new contradictions and complexities.

Ashton:The easiest part of the project was finding the general research surrounding Stationer’s Hall. It was the location of the governing body for the printing industry in its prime, so hundreds of primary and secondary sources mentioned it. It was also very easy to work with my classmates. We were all in the same major and knew each other. Therefore creating our draft proved easier than I thought it would be. The hardest part of the project was narrowing down our research to only a few sentences. We didn’t want the draft to be too long and tedious. Our group had five pages of research after we were done! We had grown to love every fact we learned about Stationer’s Hall; having to depart from some of those facts and only include the essential ones was heartbreaking.

CURAH:What kinds of things did you learn? (about the early modern period, about scholarship, or about yourself)

Emily: Prior to my work with the Map of Early Modern London, my knowledge of the early modern period was minimal at best. Therefore, before I could delve into the specifics of brothels in early modern London, I had to do a fair amount of research to lay groundwork. Even with this extra layer of research, I found that I could successfully set a schedule for myself and stick to it. That came as a surprise, since up until that point I’d never conducted such an extensive research project. It made me feel like I could handle taking on larger projects in the future. I also learned that independent research can sometimes be lonely and totally overwhelming; I was grateful for the frequent reassurance I received from my advisor that I was taking the proper steps and doing enough, even when it felt like I wasn’t.

Ashton: I had never done research quite like this before, and I learned quickly that there is an abundance of information available regarding anything one wants to research. That’s why narrowing down the research that pertains to your specified subject can be difficult. The filters and advanced search techniques our NC State librarians taught us were helpful. Databases like Early English Books Online (EEBO) were also important. As far as the early modern period itself, I learned about the Great Fire of London, one of the most important events we encountered. The fire burnt down Stationer’s Hall and destroyed most of its important documents. I learned many things about myself, but the most lasting thing I learned was my passion for early modern research. I had always loved it (I have an affinity for King James I), but this project fed my passion. It allowed me to explore some of London’s greatest buildings while also focusing on one small one that had a big impact during my favorite period of history and literature.

CURAH:Did you make any discoveries along the way?

Emily: During my research, I attempted, with increasing difficulty, to find the exact locations of the brothels listed in John Stow’s Survey of London. I came to learn that brothels were often conflated with other public houses (such as taverns and inns), and the more I tried to parse out what brothels were and how they functioned in the early modern landscape, the harder it was to draw clear distinctions between the various types public spaces. This idea of geographical ambiguity formed the basis for my Honors thesis, as I analyzed Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure with the knowledge I had acquired about prostitution in early modern London.

Above all, MoEML helped me understand London’s history—and history in general—in new ways. My research forced me to conceptualize history with geography at the forefront, which was something that I had never done before.

Ashton: My group discovered a source that proved to be everything we needed and more: Cyprian Blagden’s The Stationer’s Company: A History, 1403-1959. This detailed history gave us facts we would use for the majority of our project. Stationer’s Hall moved locations four different times during the early modern period. After the Great Fire of London, the Stationer’s Company set up headquarters in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital for 28 months during the reconstruction of the hall. At the end of the 17th century, the Hall generated revenue from renting out the premises for dances, dinners, and lotteries. This information was the most essential, and it steered our research into the right direction. The discovery of this source was pivotal for our research.

CURAH: How has the project helped you in your career goals?

Emily: My work with MoEML taught me a breadth of new skills that I use at my current place of employment. For instance, part of my job requires that I carefully examine primary source documents to verify historical dates and events. Verification was a major component of my brothel and prostitution research. Conduct ing thorough research and dealing with conflicting ideas also are useful abilities. They help with my work at a state historical society.

MoEML also gave me insight into the nature and intensity of humanities research, which is useful given my plans to attend graduate school in the near future. If I had any doubts about continuing my education, doing research for MoEML solidified not only that I would be able to do it, but also that I might actually be able to do well at it.

Ashton: I am now a high school English teacher in my hometown, and the things I learned from this research project have helped when teaching my students about how to conduct their research. I encourage them to stick with it and not get overwhelmed when presented with the abundance of information, something I had to learn to do myself. My next step is to go to graduate school and achieve a Master’s in English, and surely my research with MoEML will resurface and the tools I used within this project with help me with my further research projects in graduate school.

CUR Councilor Ian F. MacInnes is MoEML’s U.S. Agent for Pedagogical Partnerships. If you have an interested student or are thinking of working with MoEML in the classroom, please contact him.

cover photo: Programmer Joey Takeda, Student Emily Allison, and MoEML Director Janelle Jenstad with a replica of the Agas Map of London in the University of Victoria offices of MoEML

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Mentoring Beginning Students in Humanities Research

Recently, a professor in the history department came to me with a question: “How do I mentor a freshman history student in research, when this student has none of the skills required to do original research in history?” The question arose because one of our Undergraduate Research Fellows – first-year students selected to participate in a four-year program of vigorous involvement in research on the basis of a competitive application process – had approached him asking if she could work with him. Because the majority of our URFs are interested in social science, education, business, and STEM research, he had not encountered such a request before. While experienced in mentoring upper-level history students in research, he had no game plan for working with a first-year student with, as he put it, “no skills.”

This is a challenge for a lot of us working in the humanities. In other fields, such as laboratory sciences or education, the apprenticeship model, in which early-stage students interested in research join a group, and then learn by watching other, more experienced student perform protocols and discuss outcomes, gradually building their own responsibilities and skills within the group, makes it relatively straightforward to include inexperienced, novice students in the research culture. In the humanities, where we are more likely to work alone, and even the most basic data collection requires expertise in such skills as paleography, archival searching, and language translation, mentoring a first-year aspiring researcher can seem like a burdensome and impossible task.

My own experience has taught me that like so many other things, successful mentoring of entry-level student research in the humanities is all about clear communication and close listening. Here, I am condensing a few of the main points from my conversation with my colleague from history, which he later reported to me were quite helpful in getting started with his eager, but unformed protegee.

Motivations matter

Begin by asking the student to talk about what drove them to come talk to you about research opportunities. Are they part of a program (such as our fellows, or an honors seminar) that requires them to meet with professors and discuss research? If so, what are they hoping to get out of the experience? Do they want to build skills? Are they looking for a line on their resume? Are they driven by curiosity about the field more generally? This is the listening phase – you will get a good sense of whether this is a student who would be engaged and interesting to work with. I think it’s always okay to say no, though best if you can point them towards some other avenues (other faculty, a course that the department offers, a student-run organization) for exploration.

Ask about their existing skills

We tend to assume that first-year students have no skills, but especially with the kind of ambitious students who actually overcome the immense anxiety barrier to come talk to you in person this may not be the case. For example, when I was first mentoring a first-year art history student, in my initial conversation with her I learned that she had taken four years of high-school Spanish and done a service project in Guatemala. Her language skills made her a great research assistant. In the case of my colleague’s history student, she really did have very few skills, but her enthusiasm and her openness to learning meant that she ended up doing some very good bibliographic research for him. All he had to do was show her how to use the various search tools, give her some instruction in Zotero, and she was off to the races.

Define expectations

This is probably the most important part of the conversation you’ll have with the novice researcher. What are the student’s expectations in terms of time commitments and learning outcomes? Do they want to have a presentable product at the end of the year? Be a co-author on a paper? Get paid? Get credit? On your end, you also need to be clear: what kinds of tasks can you imagine the student performing? What are realistic outcomes for the work they’ll be doing? If you’re thinking, “Great, this student can scan and process documents” and the student is thinking “I’m going to see my name in print” this could lead to some trouble down the road, so it is important to get this out in the open. I think it’s always perfectly fine to do as my history colleague did – start the student on what a more experienced researcher might consider the boring ground-work – putting together bibliographies, searching databases, and compiling easily-accessible information. The important thing is that the student understands how their work fits into the larger research project. My first-year Spanish-fluent student ended up getting a thank-you in the acknowledgement note in a published essay, and for her that was exactly what she expected, and therefore quite gratifying.

Use peer-mentoring

Do you have a more advanced student, perhaps a senior working on a senior thesis, who might serve as a role model and near-peer mentor for your novice student? In many disciplines (and also in the humanities where they are practiced collaboratively, especially in Europe), groups of researchers at all levels working on related projects regularly meet and discuss their progress. Consider getting your research students together on a regular basis to talk. This way your own research process is made transparent to the students, and you’ll have a better sense of the progress they’re making, but above all, the less experienced students will be able to imagine where they might be in a year or two.

Benefits

While it is no doubt true that first-year students and others new to research in humanities disciplines do not come through the door with the types of skills and understandings that allow us to do our work at a high level, this does not mean that they cannot contribute. Starting them off with very basic tasks, but contextualizing those tasks through regular conversations about the overall progress of the research, we initiate them into the culture of humanities inquiry. All too often, students have been told “this is how you write a research paper” without really learning the WHY of research, that is to say, they have been shown the process but not given any insight into the motivations and concepts that drive the process. Getting a first-year student inside the machine takes a little effort, but once there, they tend to get very excited about doing research (way more excited than you might expect, given that all they’re actually doing is scanning documents or doing data entry, or whatever), and they learn, intrinsically, both the hows and the whys of your discipline.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Materials Matter: Humanities and STEM Work together in Innovative Program

Because human culture has a material element, the material world offers an important connection between the arts and humanities and STEM fields. This connection fuels Binghamton University’s new transdisciplinary research group: Material and Visual Worlds. Materials are part of everyday life, yet their physical properties, social histories, and conditions of formation are opaque to most of us. And academics rarely study these varied aspects of materials in concert. With support of a Humanities Connections grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities, we at Binghamton are creating a suite of undergraduate research and general education courses to connect the humanities with STEM fields focused on materials.

The project

Our team includes a cultural anthropologist, a classical archeologist, a graphic designer, a physicist, an engineer, and me (as Director of Undergraduate Research and an interdisciplinary scholar). We are creating spaces where students can consider innovations in the development and use of materials as products not only of elemental processes and scientific experimentation but also of human needs and desires, and of historical forces.

After one year of planning, we developed a pilot course, Materials Matter, that was team taught in Spring 2018 by a humanist (Roman archeologist Hilary Becker) and a scientist (physicist Todd Rutkowski). The course focused on one material: pigments. It taught foundational concepts of the physics of light and color and technical methods of analysis, as well as analytic methodologies of the humanities. These methods included interpretations of textual and artifactual evidence, and theorized understandings of relationships between people and the material assemblages with which they are enmeshed. Students applied scientific tools like X-ray fluorescence to the study of pigments used in ancient and modern times. They also practiced techniques of fresco painting and mixing pigments with different binders by hand, comparing their characteristics. Later, they visited our project partner, Golden Artists Paints in New Berlin, New York, and learned how scientists and artists work together to develop new paint formulations. Their experiences reveal how transdisciplinary study is not just a luxury of the academy but also a wider key to innovation.

Challenges

While students loved our pilot course, we are still refining our approach. From the outset, we wanted to have students analyze glass and ceramic materials as well as pigments. We also want to scale up the 20 seat seminar to a large lecture hall style sectionalized course to provide more students with this experience. But we don’t want to sacrifice the experiential nature of the course activities or the assignments that allow students to formulate and investigate their own questions. An undertaking of this scale has taken a massive orchestration, and our university structures don’t always make it easy. For example, how do we support the instructional expertise we need to teach science and humanities rigorously in one course? How do we support TAs from each area to lead discussion sections and labs? And how do we catalogue such an integrated course in our bulletin?

Development

Dr. Pamela Smart, my colleague on this project, has led the second iteration of Materials Matter. For the first time at Binghamton, we have created a course designated as both laboratory science and aesthetics general education. To support the course, we have assigned one TA from art history and one from chemistry to lead separate sections. Using our NEH award, we hired a a post-doctoral student to formulate and test each lab exercise. We’ll also be inviting guest lecturers to contribute their expertise. Golden Artists Colors will again contribute to the course, and we are bringing in our second industry partner, Corning Museum of Glass. Students will work on a lab custom designed by their chief scientist Jane Cook and curator Marvin Bolt, and then take a field trip to the museum. We will also carefully assess our course through pre- and post-course surveys and focus groups of students and faculty.

Future plans

Ultimately, we want to show undergraduates how to combine research techniques and perspectives from the humanities with those of the sciences. The next planned course will be a first-year research immersion experience, a two-course sequence that will be part of Binghamton’s new initiative, the Source Project. This initiative teaches first-year students how to do research in humanities and social sciences. It also offers courses like Materials Matter which bring these fields into mutually enhancing conversation with STEM fields. For example, a first-year student from the Spring 2018 course chose to ask why red ochre was used as an adulterant with cinnabar in wall paintings in Roman villas. He answered the question by considering cinnabar’s chemical as well as economic properties. Asked to reflect on his experience doing this work he concludes, “By combining the humanities and sciences, I was able to ask unique questions, go further in-depth, and expand more than I would have been able to otherwise. The humanities and sciences need each other in order to tell a complete story.”

Implications

The challenges we face in integrating STEM and humanities have implications not only for teaching and learning but also for the ways we go about organizing research. Over the past two years we have seen how the intellectual labor of our team has spurred new relationships and integrative research projects for faculty and staff. And we are pleased that our first doctoral student assistant received a post-doc position to work on a new interdisciplinary curriculum at another public university. This project has deepened our conviction that the most compelling and productive way to foster a liberal education is through integrative, experiential coursework that goes beyond the boundaries of any one discipline. If you’d like to hear more, we will be presenting our work in a panel at the AAC&U annual conference later this month with other like-minded colleagues creating similar experimental courses at their institutions.

Creating a Web Version of a Medieval Book of Hours: Reflections from Student Researchers

Sometimes a single item in the archives can be the basis for an extended student project. This is how Kathleen Dusseault at Truman State University found herself creating a web version of a medieval book of hours in the library’s special collections. Dusseault worked with mentors Dr. Jon Beck (computer science) and Amanda Langendoerfer (library). Drawing on translations created by a former Truman student, Lauren Milburn, Dusseault designed and created a permanent addition to the library’s website. CURAH tracked down both Kathleen and Lauren and asked them about their work.

CURAH:How did you get involved with the project?

KD: I became involved with the project due to a frequent exposure to the materials located in Truman State University’s Special Collections and Museums Department from a couple of different art history courses. As I continued to pursue a degree in Art History I needed to complete an internship that involved elements of art history in some way. I also started working in Special Collections starting in the fall of 2017, and over the course of that year I reflected on what I could do for an internship. In the spring of 2018 I took a week long digital humanities class that taught the students some html and worked as a class to develop online resources that helped make something more interactive or easier to use. My group worked on making a site that would allow for students to see all the art prints that can be checked out visually instead of having a list of artist and title. While I did not work on the coding for that website, I found myself interested in developing something that would be useful for future students and others while at the same time working on a new skill.

This brings me to the project itself. I knew that I wanted to create a website (something that I had never done before), but I wasn’t sure on what precisely or where. I brought the idea up with the head of Special Collections and Museums, Amanda Langendoerfer, and she suggested several different books or exhibits that would work well for such a project. I was drawn to our one Book of Hours because of my previous interactions with the manuscript due to my art history classes and the work that former student Lauren Milburn had completed on it.

LM: As I was pursing my Classics degree, I developed an interest in sacred religious texts. When it came time for me to complete my

Capstone, my Classics department mentors suggested that I examine The Book of Hours in Truman’s Special Collections. After an initial examination of the manuscript we decided that transcribing and translating the text would be a challenging endeavor that would benefit future students. At the time having a digital copy of the manuscript was a long-term goal. Kathleen’s dedication and hard work made this dream a beautiful reality.

CURAH: What exactly was your part in the creation of the website?

KD: Years earlier the scans of the manuscript were taken in TIF format (for preservation) and a JPEG format (for uploading digitally) excluding certain blank pages. One of my goals, however, was to have the book be viewable outside of Special Collections just the way that it would be seen within, except digitally. With the help of Annie Moots (the Special Collections digital librarian) I got to scan the original pages that were missing (all of which were just blank pages not included in the original scan). I inputted all the JPEGs into a plugin called 3D FlipBook which accomplished this goal. I then researched Books of Hours in order to add content to several pages. I placed all content onto the WordPress site myself. The only other thing that I was not a part of was the translations by Lauren Milburn. In order to create that portion of the website labeled as Translation and Transcription I added the already written content myself but kept the way that Lauren formatted the writing (for her capstone). Originally, however, they were two separate text documents. The biggest change I made was placing the transcription on the left, the corresponding scan of the manuscript, and the translation on the right.

LM: For my Capstone project, I transcribed and translated the Latin within the manuscript. In addition, I deciphered and indexed abbreviations, decoded the format of the text, and created footnotes to provide context for the readers.

CURAH: What were the easiest and hardest things about the work you did?

KD: The easiest part to this project was adding content to the website. After looking at several books on the subject I found it easy to narrow a focus down on what sort of information I wanted to provide. I also had a lot of fun at the end of my project doing some user testing with library staff and friends who volunteered. I found that as I went along with the project I knew where to click to find certain information and it didn’t seem to work the same way with those who tested out the site at the end.

The hardest part that I had was working with Lauren Milburn’s transcription and translations. I was unfamiliar with the structure of quires (which is how Ms. Milburn had divided the content of her translation and transcription). In order to accomplish the task of putting the work online I first needed to understand how she had created the translation and transcription. Once I became more familiar with her work this was no longer an issue.

Formatting was another thing I struggled with on occasion. This was due to my lack of experience with WordPress, but after working on a couple of different pages and developing pages with a website builder plugin called Elementor I wasn’t finding this to be as much of an issue.

LM: The easiest part of working on this project was engaging with the subject matter itself. As a Roman Catholic I found translating the familiar prayers and sections of scripture exceptionally enriching. It also felt incredibly humbling to connect with a text that was a sacred source of meditation and prayer for the original owners. The hardest part of working with the text was deciphering the abbreviations and learning the writer’s Latin shorthand. Certain phrases and words were often shortened within the text because the prayer or piece of scripture had been stated in–full earlier within the Quire.

CURAH: What kinds of things did you learn?

KD: There are many different things that I learned while working on this project. As I only had a beginners knowledge on what a Book of Hours is and its purpose there was a lot of content that I learned in order to make the website. I also learned a significant amount about how to work with WordPress, which I think will be beneficial later on in life, and I learned quite a few things about myself. At the beginning there were three goals for my project. I wanted to make the Book of Hours visible outside of the reading room at Truman State, have the transcription side by side with original pages, and add the additional content for those who would like to learn more about such a manuscript. It’s from gathering this content and presenting it that I learned more about myself, surprisingly. I found that altering my perspective on the information was difficult for me. What I mean by this is that having even the slightest knowledge on the subject had me skipping over important pieces of information that would be necessary to people just learning about what is a Book of Hours. I found myself constantly looking over the information to find these gaps and sometimes completely missing them. To combat this I had users that volunteered to test out the site and read the content within it to find these spots where I may have missed crucial information. Watching users read the content and listening to their questions also let me know where information should be located or added. Due to this project I also thought more about future careers and potentially going into the field of museum registrar or an education route (such as history or museum).

LM: This project enabled me to learn about the process of creating Books of Hours and their accompanying illuminations. In addition, I learned how to carefully work with and handle the fragile vellum. In doing so, I was able to honor the past while working to provide a resource for students in the present.

CURAH: Did you make any discoveries along the way?

KD: This kinda relates back to what I learned, I probably wouldn’t say that I learned anything earth shattering about the Book of Hours that I worked with, but I did learn a lot about myself. I really enjoyed creating educational content that can be used by a variety of different people (i.e. researchers, students, faculty, scholars, anyone really). I also note in the site that within the border design on two of the illuminations have a particular flower in the border. That was an interesting tidbit that felt a little bit like a discovery to me.

LM: One fascinating aspect of working with this text was coming into contact with little French notes written in in the margins and in the back of the manuscript. Discovering these notes written by the owners made this project magical. The process of analyzingthe illuminations was another intriguing facet of this experience. Particularly, in regards to the ways in which ritual played a part in the owners’ mediations. For example, there is an illumination in which the face of Mary (the mother of Christ) has been “rubbed” away. I learned through this process that the owners must have repeatedly touched the illumination in this spot as they were praying.

Finally, the greatest discovery I made while completing this culminating project was the immense value in studying Classical languages. The time I spent studying Latin, Greek, and working on this Capstone project at Truman shaped who I am as a human and teacher. I am currently finishing a graduate degree in Applied Behavior Analysis and I still utilize the tools I cultivated as a Classics student every day. Specifically, this project and field of study enabled me to develop problem solving skills and the ability to analyze complex texts. I am extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to learn from all of the professors in Truman’s Classics department and to have had their mentorship throughout this project. The trajectory of my life and career has been profoundly impacted by their support and knowledge. I am also exceedingly grateful to Kathleen and her dedication to digitally preserving this manuscript. She has done such stunning work and has given an amazing gift to our university.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

New Travel Award for Undergraduates in Arts & Humanities: Call for Applications

The Arts & Humanities Division proudly announces an important addition to our funding programs! Joe Trimmer, a founding member of the Arts and Humanities Division, and his wife Carol have established the Trimmer Travel Fund. The fund supports an annual award to support international travel for undergraduate research presentations in the Arts and Humanities. The Trimmer Travel Fund anticipates making its first award to a student presenting at the May 2019 World Congress on Undergraduate Research in Oldenburg, Germany.

The Donors

Joe Trimmer is Professor Emeritus of English at Ball State University (Muncie, IN) and the founding director of the Virginia B. Ball Center for Creative Inquiry. He is the author of numerous books on literature and culture, and a contributor to 20 PBS documentaries. He has served on the CUR Executive Board as the Arts and Humanities Division Representative, and as a member of the Board of Directors of Indiana Humanities. Carol Trimmer has served as the Outreach Coordinator for IPR, Ball State University’s NPR member station, as well as a member of the Board of Directors of Arts Place, a regional Indiana arts organization, and Muncie’s nonprofit Gallery 308.

The National Office and the Arts & Humanities Division are deeply grateful for Joe and Carol Trimmer’s generosity and commitment to undergraduate research. Their gift is an important step in supporting arts and humanities student participation in international research conferences.

How to Apply

The Calls for Submissions for CURAH Travel Awards are now open. Please encourage students accepted to the World Congress to apply for the Trimmer Travel Award:

The long-standing CURAH Student Travel Award will continue to sponsor students presenting at NCUR and POH:

Applicants should submit the completed application form and all attachments as per the instructions to the CURAH Division Chair, Dr. Maria T. Iacullo-Bird by the deadline of Monday, February 25, 2019. Award announcements will be made by March 15, 2019.

Rewards and challenges of UGR in Art History and Philosophy (from 2018 CUR Biennial presentation)

Centre College faculty Amy Frederick (Art History) and Eva M. Cadavid (Philosophy) presented at last summer’s Biennial CUR conference. Here they reflect on some of the followup questions the audience asked about the rewards and challenges of incorporating undergraduate research at a small liberal arts college.

CURAH: What were some of the challenges you faced when you started doing undergraduate research at Centre, a small liberal arts college in a small town?

Eva: The biggest challenge for me was thinking about what undergraduate research looks like in philosophy. I found myself thinking that it either had to look like the sciences or feeling like my students would have to have all sorts of expertise if they were to genuinely work in my areas of research. Philosophy is normally seen as a solitary endeavor. It is not. If it was, why would we share our work at conferences and try to get feedback from others? Admitting that was my first step to identifying how to foster research with students. Students can collaborate with each other and with faculty while still being responsible for research that is theirs.

Amy: I absolutely agree that scholarship in the humanities has traditionally been solitary, which can be a challenge when thinking about conducting research with undergraduates. As an art historian, I find that our geographical location at Centre also presents obstacles for meaningful undergraduate research. Our closest regional art museums are the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, KY (89 miles away), and the Cincinnati Art Museum (121 miles away). My first thoughts upon arriving at Centre turned toward attempting to rectify this situation for my students. A common thread through my ongoing efforts is to provide opportunities for them to interact with objects both inside the classroom and as part of independent research projects.

CURAH: How are you addressing some of those challenges?

Eva: I am still trying to figure out what I am doing with UGR. Some of my students are doing the traditional independent study where they develop an interest they have over a semester and either revise a paper or write one. But I only work with students who are really focused on the topic and who agree to present their work publicly and revise their final papers. This seems to me a more traditional (and very valid) way of doing UGR with humanities students.

Some of my students have become an integral part of my research, which intersects both philosophy and social science. We have a research team with students staking their skills and developing a main project under the umbrella of our overall research but also very much knowing that they must help others on the team as needed.

Most of the students who have worked with me over the last 4 years are not philosophy majors. Some are and some declare a minor after working with me for a few semesters. They bring a lot into our research and they also develop a lot of philosophical skills that they then take with them and apply in their chosen fields. They bring creative and fresh perspectives and challenge me to defend and to rethink the way I do philosophy.

Amy: When I arrived at Centre, I was happy to find that the College owns a small teaching collection of art. Two years ago, two students and I began the long process of creating a database for the College’s ceramics collection. While work had been done on the collection in preceding years, it was never a primary focus for any one person or office. The students learned new vocabulary and how to create and use metadata. The students and I regularly discussed how each step of the process would inevitably lead to twenty more steps that they hadn’t initially considered. We all had to readjust our expectations, especially me. By the end of that first summer, one student was able to put all of the digital photographs of the objects into a OneDrive folder, and the second student had been able to input most of the already-known information into an Excel spreadsheet. No supplementary research was done, and we did not get through even a description of each object for our spreadsheet, much less a decision about how this information would eventually be presented to the public.

This past summer, another student took up the task. Work in the interceding two years had been sporadic and inconsistent, and often without parties talking with one another. We now have (incomplete) databases in OneDrive, GoogleDocs, Excel, AirTable, and an old image database. We have old file folders in a variety of locations on campus. I think I have become more realistic about the scope of this project, and more enthused by the continued student interest in working on it. I am thrilled that these students are learning to “do” art history. We will keep making small steps forward.

CURAH: What aspects of your experience might be applicable at other institutions?

Eva: Mostly, it has been very successful but it works best when I trust the student and give them the freedom to fail. It is also an endeavor that takes time. Although independent studies can lead to success in only a semester, for creating a research team, it helps to have students stay with the team over a few semesters, help train each other, and stake an area where they then train the next person. It may sound weird to think of applying this to philosophy, but it is doable – whether it is developing bibliographies, websites, documents, etc.

Amy: For me, I think it is important to discover and then utilize what you have. What are your available resources for undergraduate research (on campus, in the community), even if those resources may not be what you expect or are familiar with?

———————

What are your early experiences like in integrating undergraduate research in the humanities? Let us know in the comments or by contacting the editors at editors@curartsandhumanities.org.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Letter-press poetry merges art and creative writing in interdisciplinary course

Poetry and fine art have a long history of fruitful interaction. At

Albion College, professors Anne McCauley (art) and Helena Mesa (English) have taken advantage of the natural connections to create an inspiring example of interdisciplinary creative activity: a course called “Visual Poetry,” where students print broadsides of their own poetry on three Vandercook proof presses. There are several valuable results of this kind of interdisciplinary creative activity.

Revision

Some students approach the class primarily as artists and others as creative writers. But both learn the true meaning of revision and the value of meticulous attention to detail. “No one wants to spend hours writing and revising a poem, setting type, printing a poem, trimming and prepping a package or broadside, only to discover that she misspelled honeysuckle or that he omitted a period,” says Mesa. “The process demands that we slow down and proofread-proofread-proofread before we say something is ‘finished’ or ‘published.’ Setting type is itself a slow and careful process. “Hand setting type requires a lot of attention to detail and patience,” McCauley says. “The job is a meticulous one, often tedious. This exercise and the results make us aware of how much we take for granted the words we consume online and in hard copy.”

“In these broadsides words are physical and the voice we hear when we read them feels present.” — Anne McCauley

Reflection

This interdisciplinary creative activity also promotes new kinds of reflection on the craft for both the artists and the creative writers. “ Poets rediscover what space can do for a poem,” says Mesa — “the placement of a line, of a stanza, of the poem on the page affects how we read, and in printmaking, that space provides students a new conceptual understanding of space.” Artists find their ordinary experience in printmaking amplified. “Every step is deliberate and time intensive,” says McCauley. “And there are no ‘happy accidents’ in letterpress printing. It takes a lot of experience on these presses to feel confident in experimenting with the process, the materials and the imagery.”

Challenges

Because it demands a new approach to the material, a course featuring interdisciplinary creative activity like “Visual Poetry” is challenging for students. “It’s one thing to write a poem, workshop it, show it to some friends or family, and potentially, file it away forever,” says Mesa. “But when you write and revise a poem for display, as a broadside or small book, the process can raise new anxieties about whether or not the poem is finished. That is, there’s a tension between the intimacy of a private poem, a hidden poem, and a poem meant for the public, meant for display. And while we discuss the reader in all of my workshops, it’s easy to hide a poem and never show it to anyone after the semester ends. It’s less easy to hide a poem that’s designed to hang on a wall.” Artists experience their own challenges. “Artists initially anticipated it would be a more direct, less time intensive process,” says McCauley. “But first they had to generate and organize the words to create their poetry. With this combination of challenges, the writing and the preparation to print, the physical investment was (mentally and physically) exhausting and exhilarating. After working with an artist/writer at a press for several hours, I found that I often had to provide an additional dose of patience necessary when everything seemed to be going wrong on the press.”

Creative exchange

The most important benefit of interdisciplinary creative activity is the opportunity to incorporate different approaches and ways of thinking. “Visual Poetry” allows students discover fundamental artistic processes. “Art students, like writers, build on imagery,” says Mesa. “They create things that mean something, and detest clichés, especially the easy ‘put a bird on it’ clichés. Our artists had just as much to say about the imagery within a poem as our writers did, which gave us a common ground to start the conversation.” Students also benefit from the interaction between experts in two different fields. Both McCauley and Mesa say that the collaborative classroom gives their students a better and different version of themselves as teachers. They are conscious about marrying their skillsets. And their collaboration makes for projects that Mesa says “are more inventive and challenging than we could ever envision on our own.” Both instructors find the class energizing, despite the additional time it takes. Mesa muses, “Perhaps it’s tapping into a long history of ekphrasis—art written in response to poetry—that engages our creative selves in a new way, which invigorates my teaching energy.”

Do you have examples interdisciplinary creative activity with students? Let us know in the comments or directly to the editors@curartsandhumanities.org

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

$1,000 prize for undergraduate research to be awarded by HERA

Opportunities for undergraduates to present alongside faculty are rare in the humanities, but the Humanities Education and Research Association (HERA) is notable exception. Their annual conference welcomes “educators at all levels… including undergraduate/graduate students.” Best of all, HERA sponsors a $1,000 prize for undergraduate research. The prize goes to the best undergraduate paper at its annual conference. HERA also gives a smaller award to the student’s attending faculty mentor.

Opportunities for undergraduates to present alongside faculty are rare in the humanities, but the Humanities Education and Research Association (HERA) is notable exception. Their annual conference welcomes “educators at all levels… including undergraduate/graduate students.” Best of all, HERA sponsors a $1,000 prize for undergraduate research. The prize goes to the best undergraduate paper at its annual conference. HERA also gives a smaller award to the student’s attending faculty mentor.

The 2019 conference is in Philadelphia, March 6-9. Its theme is “Highbrow, Lowbrow, Nobrow: Research and Aesthetic Values in the Humanities.” But HERA encourages participants to interpret their theme as widely as possible. The deadline for proposals (150-200 words) is January 25, 2019.

Last year’s prize for undergraduate research went to Leann Christopherson from San Francisco State University for her paper, “‘Everything was a Pretext to Arrest us’: Communicating Intersectionality through Transgressing Literary Borders in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.” Her faculty mentor is SFSU English Professor Sarina Cannon.

More information is available from HERA’s conference page on their website. If you are a student interested in submitting your work, you should check out CURAH’s guide to writing an abstract.

Do you have information about an undergraduate conference opportunity or a prize for undergraduate research in your area? Let us know using the comments or by direct email to the editorial team.