We are fortunate to live at a time when museums and public collections are finally returning objects to the people and cultures from whom they were taken. Colleges and universities, large and small, often have their own collections and will continue to be a part of this process (in some cases the law requires it). As two cases at Albion College make clear, repatriation represents an opportunity for undergraduate research. Activities appropriate for mentored students include reviewing a collection, determining which objects are legitimate subjects of repatriation, and documenting them completely. The actual repatriation process itself requires communication and public relations. Its fruition serves as an important public confirmation and validation of basic research.

NAGPRA requires research

Happily, the law actually requires some research (how often does that happen!) through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) . All museums, federal agencies, colleges, and universities need to compile an inventory of Native American human remains, funerary objects, and summarize other cultural items. No university collections, no matter how small, are exempt, regardless of where the cultural items are physically located. Much of this inventory and summary work is within the capabilities of mentored undergraduates. At Albion College, for example, the inventory and summary research of student Chelsea Adams resulted in identifying a Zuni Ahayu’da, one of twin gods of war.

This was a clear case for repatriation since the Zuni consider any Ahayu’da removed from its shrine (where it retires to decay naturally) as stolen. After documenting the Ahayu’da carefully and following the NAGPRA protocol, it was repatriated in a ceremony on campus involving several Zuni elders.

Repatriation is highly collaborative

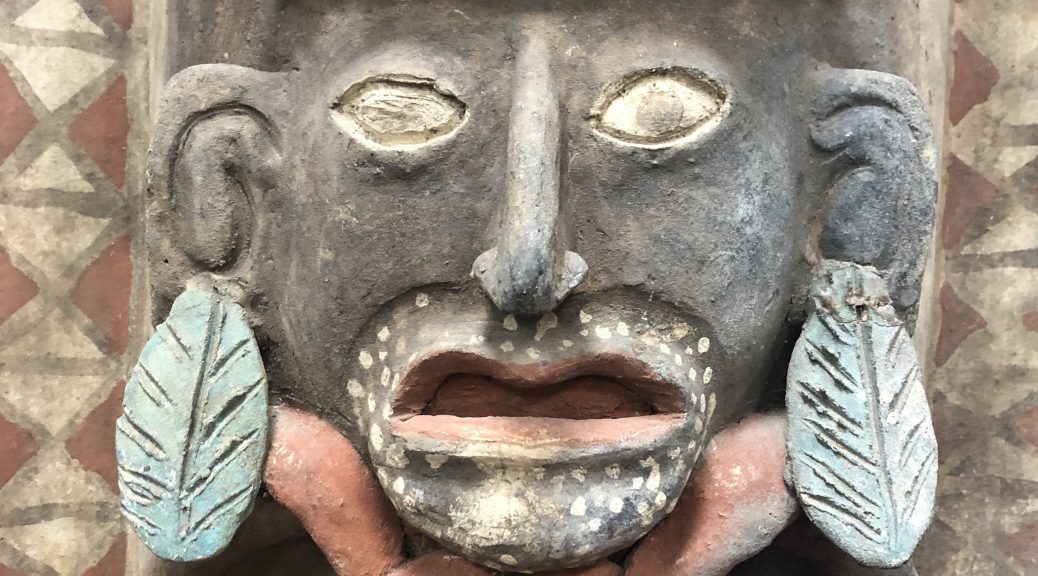

Opportunities also exist for repatriation outside of the United States. These are less formally defined than with NAGPRA repatriation, although the process can be more complicated and more collaborative. Archeologist Joel Palka (currently at Arizona State University) was using a collection at Albion College as part of his 2005 book on the Maya and identified an urn whose twin resides in Chiapas, Mexico. In 2016, he collaborated with Albion’s archivist, Justin Seidler, anthropologist Brad Chase, and Albion students to perform an instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) on the urn. Since then, Palka has helped Albion work toward repatriating the urn to Chiapas, along with Josuhé Lozada Toledo, an archaeologist and Professor of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico (INAH).

“Everyone has been extremely excited about the process,” says Meghan Webb, Albion College anthropology professor, “and it has been an encouraging process. All involved also see the repatriation as a process and opportunity to build ongoing relationships.” Webb has been working with student Dulce Aceves on a research project connected with the repatriation, which is expected to conclude in the spring of 2021.

Repatriation is scalable

These cases at Albion College make it clear that repatriation of even a single object is a major project, requiring intensive research and extensive communication. As a result, it’s possible that even small collections can potentially provide ongoing opportunities for undergraduate work. In addition, given the large number of small tasks, repatriation is a potential opportunity for a course-based undergraduate research experience (CURE), expanding the reach of the experience.

Repatriation is the right thing to do!

Finally, repatriation puts faculty and undergraduate students on the right side of history. The work of repatriation teaches students about the ethics of collections and about the history of Western colonialism and hegemony.