It isn’t often when undergraduates are granted the opportunity to connect family heritage and independent student research while bringing awareness to underrepresented fields. Sofia D’Amico, an art history major with a concentration in Asian art at Fordham University has been given this very opportunity in her project studying the work of artist Tiffany Chung. CURAH recently interviewed Sofia to learn more about her project.

CURAH: What was the nature of your project?

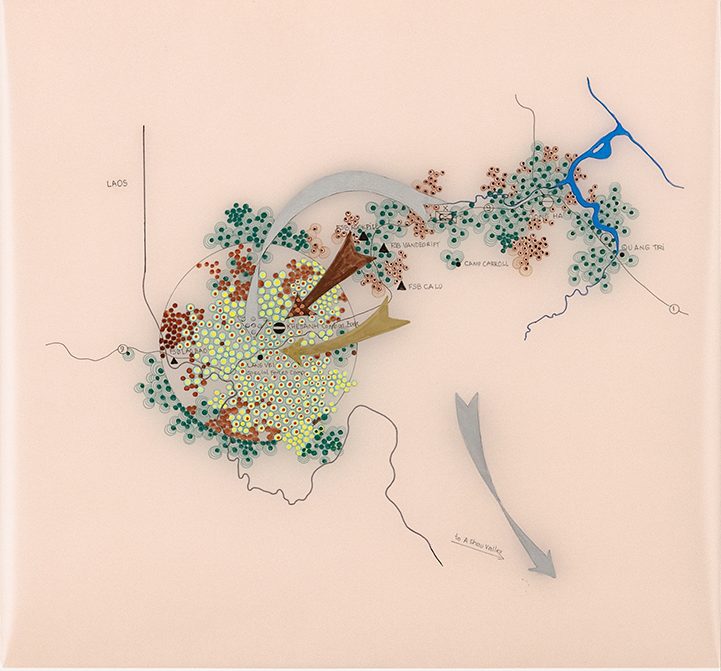

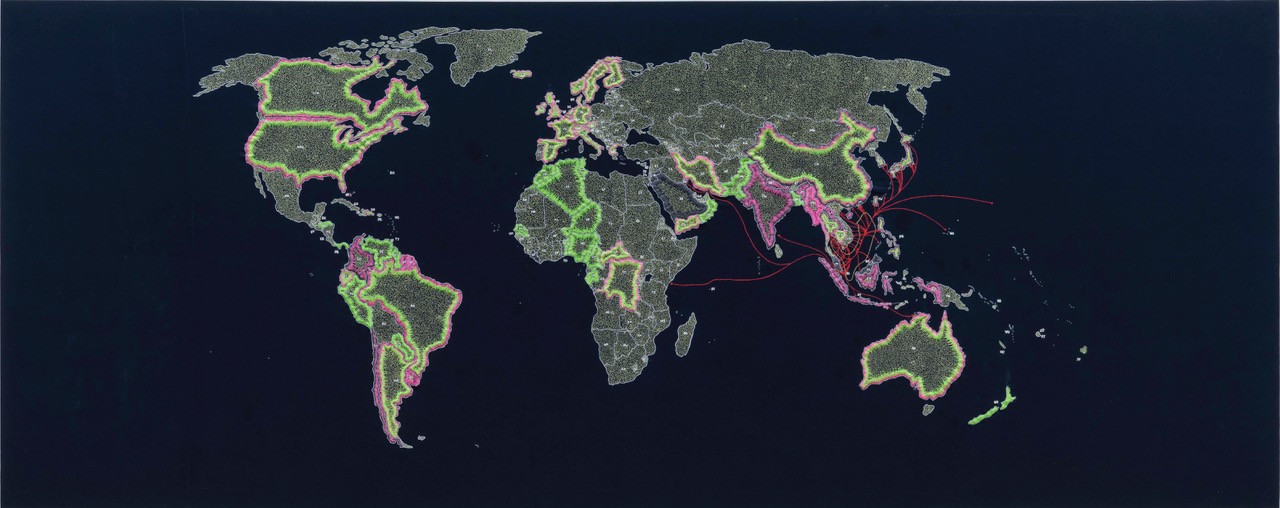

SD: My research focuses on the work of contemporary Vietnamese-American artist Tiffany Chung, especially her cartographic works which study global migration, displacement, conflict, and urban development, and their relation to history and cultural memory. Chung was born in Danang, Vietnam in 1969 and became part of the post-1975 Vietnamese Exodus of refugees to the United States, following the communist siege of South Vietnam. She currently lives and works inHouston, Texas. Her maps, rendered in attractive pastels and jewel-tones, invite viewers to question information often taken for granted, like historical memory, as tied to place, and the accuracy of conventional systems of knowledge.

I explored her work in three different spaces in 2018: a group exhibition at Asia Society Houston titled New Cartographies, which explored maps as an artistic medium, her solo-booth of work at Miami Art Basel, and her major solo-exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum: Vietnam, Past is Prologue. I considered what her works achieve in these shows, as well as her transnational artistic identity as a Vietnamese refugee, and how her life experiences have oriented her work towards an international, historical focus. I investigated such questions as, Does Chung’s work transcend nationality? What are some of the obstacles that artists from Southeast Asia encounter in establishing relevance to US audiences? And at the same time, how does Chung’s work depart from precedent and tradition? As a Vietnamese refugee is Chung expected to create work about the Vietnam War? How do Americans understand the Vietnamese, apart from the war and its cultural exports? Is it reductive to attach the label of Vietnamese-American artist to Chung when she works hard to be international in her perspective?

CURAH: What were the easiest and hardest things about the work you did?

SD: Of course, Southeast Asian art history is a developing discipline, and my research on Tiffany Chung necessitated that I conduct my own art historical study. But even in the 20th century, many Southeast Asian countries have undergone tremendous hardships. And the reverberations of European colonial legacy (stemming as far back as the 1500s) are still felt in the study of Southeast Asian art history: most writing on Vietnamese art history, for instance, has been done in French and from the perspective of European colonizers––which can of course be problematic.

Since the establishment of an independent Vietnamese state in 1945, little money has been disbursed for such cultural projects. Besides listing painters in official registries of artists, little effort has been made to maintain archives of artworks or art movements in Vietnam; certainly, as compared to western countries or even the monolith cultures of East Asia like China and Japan. But because Vietnamese art history records are rarified, there is a greater need to interview living artists than to consult written documents. I’m excited to explore this going forward.

In short, the hardest part of the research project is really its most interesting feature: that is, understanding the multiplicity of Southeast Asian art, learning about it largely independently, and communicating my findings in a way that is accurate, respectful, and sensitive to those it relates most to. Especially as an undergraduate, it’s intimidating to put research findings and original ideas out there in the global sphere. But it is also incredibly exciting to become informed in topics you were once simply curious about, which I think was the easiest part of the work. Having a connection to the work and being passionate about the topic made it easy and enjoyable to search for resources and interview specialists. I think the nature of Southeast Asian artists being understudied made it all the more encouraging to dive in.

CURAH: What kinds of things did you learn?

SD: Because my research interest was prompted in part by my own heritage, I was able to use my family history as a springboard for learning about Southeast Asian art. My mother is a Vietnamese immigrant, and, incidentally, grew up in the same city and around the same time as Tiffany Chung. I didn’t learn much about Southeast Asia and Vietnam in school (apart from the war), so as I grew up, I would ask my mom about Vietnam. But her experience as a refugee made her understandably sensitive to some topics. I grew up, like most people, knowing little about Southeast Asia and thinking that artistically it had little to offer the world. Despite majoring in art history and concentrating in Asian art, I knew virtually nothing about the art of Vietnam.

With encouragement from my professor of art history and mentor, Dr. Asato Ikeda, as well as support from my school, Fordham University, I started doing independent research. And I couldn’t believe what I had missed out on! I interned at Tyler Rollins Fine Art in Chelsea, New York––the only art gallery in the country dedicated to contemporary Southeast Asian artists. Rollins and his gallery taught me how fascinating Southeast Asian culture and history really are, as the confluence of South Asian, Indian and Hindu influences, and East Asian Confucian, Daoist, and Chan Buddhist society. And, as such, Southeast Asian and diasporic artists create work that is wholly unique in perspective, context, and content. There is so much to both say and write on the subject.

CURAH: Did you make any discoveries along the way?

SD: I definitely made discoveries which encouraged me to keep going! As simple as it is, one thing I discovered as I went deeper into my project, was how much work and research still needs to be done in this field, and similar fields to it. There is so much interesting phenomena––some tragic, some triumphant––that evade contemporary consciousness.

I began my work by focusing on one contemporary Vietnamese-American artist, but ended up branching into Vietnamese art history, clearly under-researched. From there I learned about contemporary Vietnamese history, like the Japanese occupation of Vietnam and artists who were half-Vietnamese and half-Japanese, creating art about their families’ experiences: pieces of history I had no idea about. When I found out about this occupation, I was able to bring it forward to my mother, who opened up about our family’s interactions with Japanese soldiers. This research ultimately helped me, in my study of art, as well as personally, in understanding complicated and difficult parts of history.

From here, another important discovery for me was the possibility of doing research in a way that parallels the artists’ practices that I am interested in: by sharing microhistories, individual narratives, and family experiences, and exploring what a radical act that can be.

While researching Tiffany Chung, I witnessed a four-channel video installation titled The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019) by artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen, which chronicles the descendants of Senegalese French colonial soldiers once stationed in Vietnam tirailleurs Sénégalais — and features stories written by three members of a Vietnamese community in Senegal. One portion of the video observed the tense confrontation between a half-Vietnamese half-Senegalese boy with his Senegalese soldier father, who whisked him away from Saigon at a young age and never allowed him to know his Vietnamese mother. This piece allowed viewers like me to connect with a small community and especially with individual families’ experiences, as they were affected by war and colonialism. I thought it was radical and moving to have this focus on smaller units of research like individual communities, people, and events. I’d like to carry this awareness of microhistory forward with me throughout future research in my academic career.

CURAH: How has the project helped you in your career goals?

SD: It is due to this project that I have found my art historical focus and ongoing research interest in making more familiar, to myself and others, the peripheralized stories of Southeast Asian artists within Asian art and the world’s art histories more broadly. It has helped me realize that I would like to be a part of a larger movement academically, whether that is Southeast Asian art historians, researchers of Asian diaspora, or scholars of socially-engaged contemporary art.

It’s also made more clear the need for further diversification of US art spaces. Visual culture and art act as some of the most powerful ways people understand each other transnationally. I would love to see the development of more robust Southeast Asian curatorial

programming in museums and galleries in the future, and I hope to help contribute to it someday. And it’s encouraging to see institutions like Fordham actively supporting these art historical projects. The voices of emerging undergraduate researchers are wanted and our work is important on so many levels.

I am really looking forward to meeting Sophia and seeing her present at CAA in Chicago in a few weeks (February 14 to be exact). This research is so far above the level of what people ordinarily think of when they think of undergraduate art history (all too often perceived as “art appreciation” and treated without critical seriousness), and it demonstrates wonderfully what young scholars can bring to the field with their energy, their personal engagement in the discipline, and their openness to topics outside the standard narratives of art history.