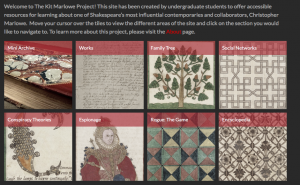

Sometimes the perfect opportunity for original undergraduate scholarship in the humanities ends up as a multi-semester digital project with a life of its own. This is the story of the Kit Marlowe Project, the brainchild of early modern scholar Kristen Abbott Bennett when she taught at Stonehill College. In essence, Kristen’s students researched and created an entire digital humanities project, from the basic TEI coding to its WordPress implementation. Each part of this process offers lessons and inspirations for undergraduate research. I tracked Kristen down at her new home in Framingham State University and asked about her experiences.

IMcI: What inspired you to create this project for your students?

KAB: My students inspired the project. I’d assigned a Scavenger Hunt so that they could do research on Christopher Marlowe and they struggled to find sites that had reliable and comprehensive information. We also discovered that there is no site that offers a curated digital collection of both Marlowe’s drama and poetry. My students and I decided to fill that gap in the context of coursework we were doing and they jumped right in.

IMcI: What kinds of research and scholarship did they need to do?

KAB: Students had to conduct rigorous research to design their web exhibits, their works projects, and to contribute to the “-ography” database we started that complements the encoded works we’ve published to date. The web exhibits required conventional library research, but at the same time, they studied web offerings to think critically about how to select information to include, present it, and write for new media. The works assignments required them to learn about editorial practices in the context of figuring out what kinds of editions they were working with and sharing that information with an audience of readers who are, like themselves, learning about Marlowe’s life and times.

KAB: Students had to conduct rigorous research to design their web exhibits, their works projects, and to contribute to the “-ography” database we started that complements the encoded works we’ve published to date. The web exhibits required conventional library research, but at the same time, they studied web offerings to think critically about how to select information to include, present it, and write for new media. The works assignments required them to learn about editorial practices in the context of figuring out what kinds of editions they were working with and sharing that information with an audience of readers who are, like themselves, learning about Marlowe’s life and times.

IMcI: This sounds difficult for anyone, let alone undergraduates! What were the biggest challenges they faced?

KAB: You’re probably expecting I’ll say that the encoding portion of the class was the most challenging. But when we have enough hands on deck, especially people like Scott Hamlin (Stonehill IT) who helped me for the past three semesters, plus enthusiastic and smart TAs, the encoding part of the course can be wonderfully exciting and satisfying. Actually, the biggest challenge is teaching students that one must be more rigorous about writing and citing well on the Internet than in a conventional writing class. That may sound like common sense to instructors, but students’ online writing models – not just Instagram and Twitter, but even their blog posts – tend to feature sentence fragments and confused syntax. One of my critical projects in this course is to persuade students that they must be model writers for others.

IMcI: But you did also teach them to code! People say TEI coding is the hardest and least exciting skill in the DH repertoire, but clearly your project proves otherwise. What did they get out of TEI?

KAB: TEI is a brilliant way to teach close reading skills in any classroom! The act of transcription alone forces students to slow down and pay attention to textual features, to the language itself. TEI encoding practices are, to oversimplify, basically a way of annotating text critically and consistently. Although we teach students annotation skills in most classrooms, they are usually not required to make decisions about what the “authoritative title” is, what printer errors one corrects, what to do about omitted signatures, or curiously spelled place names that do not exist on Google Maps (but do in Pelagios!). Moreover, these editorial decisions need to be made as a class. Students must work toward consistent encoding practices collaboratively. They understand that they are accountable for not only their own work, but that of their entire team. I hold them to the same standards in the works projects and the web exhibits, but the encoding project brings this point home.

IMcI: The fun thing about a public-facing website is watching people use it and respond. What kind of comments have you gotten?

KAB: Unfortunately, we didn’t have the comment feature working after our launch at the 2018 Shakespeare Association Conference (SAA), but I’ve received a number of compliments about the resource! The librarians at Framingham State University have added it as a featured database on the library website. I’ve been told by many colleagues that they are directing their students – both graduate and undergraduate – to the site to learn about Marlowe and his works! Overall, the feedback has been great. Moving forward, I will be open to contributions from classes at different institutions and will be happy to work with faculty to design suitable activities.

IMcI: And the project now has a life of its own, right? What happens next?

KAB: This semester my former Stonehill TA, Rowan Pereira (’19) will work on the project as an intern. She’ll be editing the two Faustus editions our Spring class published and cleaning up other parts of the site. Additionally, my sophomore-level Shakespeare class at Framingham State University will contribute web exhibits focused on Marlowe and Shakespeare’s collaborative works.

Abbott-Bennett’s students are enthusiastic about the value of the project. The following comments are reproduced with the permission of the students.

I am incredibly proud, impressed, and surprised by the work I created and published in this course. When all of the transcribing, encoding and time-consuming work was complete, and the final piece was uploaded onto TAPAS it was such a gratifying experience. It was so cool to see how the different codes interacted with the text to actually make things happen in the final product. It’s hard to describe what it feels like to see the final text with all of the various textual features as if nothing went into making them happen, but then thinking about all of the work that went into bringing the text to life.

— Justin Boure, Stonehill ’19The experiences that I had during the process of proofing, editing, and proofing again had an impact on my reading practices. I took care to read more carefully in an effort to avoid missing details that I could have gone over before. When I noticed a seemingly obvious detail on a second look through the text, it would be a gentle reminder to avoid skimming… I also became more focused on the spelling of words, the phrasing, and rhymes. When attempting to encode the text, I could not simply read the words and get the gist of what was said, but I had to analyze every letter, and could not but help notice rhyming couplets wherever they appeared. Ultimately, the proofing, editing, and further proofing served to make my reading much more methodical, detail oriented, and analytical.

— Robert, Coleman. Stonehill ’19The issue of open access is quite possibly my biggest takeaway of this course. My whole life I have had access to whatever information I wanted. My schools provided databases and resources so I could read anything I was interested in. … Making knowledge accessible to all is so important and interesting from an ethical perspective. I would like to research it more.

— Abigail Ballou, Stonehill ’19

Do you have any experience teaching with TEI or curating a digital site with undergraduates? Let us know.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.