by Dr. Jo Koster, Winthrop University

Humanities scholars and students aren’t usually taught to write abstracts like our friends in the natural and social sciences are. That’s because in the humanities, full pieces of discourse are preferred to short, condensed summaries. But in many cases you will NEED to write an abstract for your work—and a lot of what your colleagues in other disciplines know can help you.

Let’s start with the basic questions.

What is a descriptive abstract?

A descriptive abstract is the summary of work you have already completed or work you are proposing. It is not the same thing as the introduction to your work. The abstract should give readers a short, concise snapshot of the work as a whole—not just how it starts. Remember that the readers of your abstract will sometimes not read the paper as a whole, so in this short document you need to give them an overall picture of your work. If you are writing an abstract as a proposal for your research—in other words, as a request for permission to write a paper—the abstract serves to predict the kind of paper you hope to write.

What’s different about a conference paper (or informative) abstract?

A conference abstract is one you submit to have your paper considered for presentation at a professional conference (CURAH maintains a growing list of these opportunities). The conference organizers will specify the length — rarely be more than 500 words (just short of two double-spaced pages). In an ideal world, you write your abstract after the actual paper is completed, but in some cases you may write an abstract for a paper you haven’t yet written—especially if the conference is some time away. Because the conference review committee will usually read the abstract and not your actual paper, you need to think of it as an independent document, aimed at that specific committee and connecting solidly with the theme of the conference. You may want to pick up phrasing from the conference title or call for papers in the abstract to reinforce this connection. Examine the call for papers carefully; it will specify the length of the abstract, special formatting requirements, whether the abstract will be published in the conference bulletin or proceedings, etc. Abstracts that do not meet the specified format are usually rejected early in the proceedings, so pay attention to each conference’s rules!

How wedded are you to the abstract you submit?

An abstract is a promissory note. That is, you are promising that you can and will produce the goods in the paper. Particularly in the case of a conference abstract, the organizers will make up a session based on the contents of the abstract. If you propose a paper that says you will use Foucault to comment on post-colonialism in Heat and Dust” and then show up with a paper on “Metaphors for Spring in A Bend in the River,” your paper may not fit the session where it was slotted, and you’ll look silly—and those organizers may not ask you back. While some divergence from the promised topic is acceptable (and probably inevitable if you haven’t written the paper when you submit the abstract), you need to produce a paper that’s within shouting distance of your original topic for the sake of keeping your promise.

The Five Step Process

Descriptive abstracts are usually only 100-250 words, so they must be pared down to the essentials. Typically, a descriptive abstract answers these questions:

Why did you choose this study or project? What did/will you do and how? What did you/do you hope to find? (For a completed work) What do your findings mean?

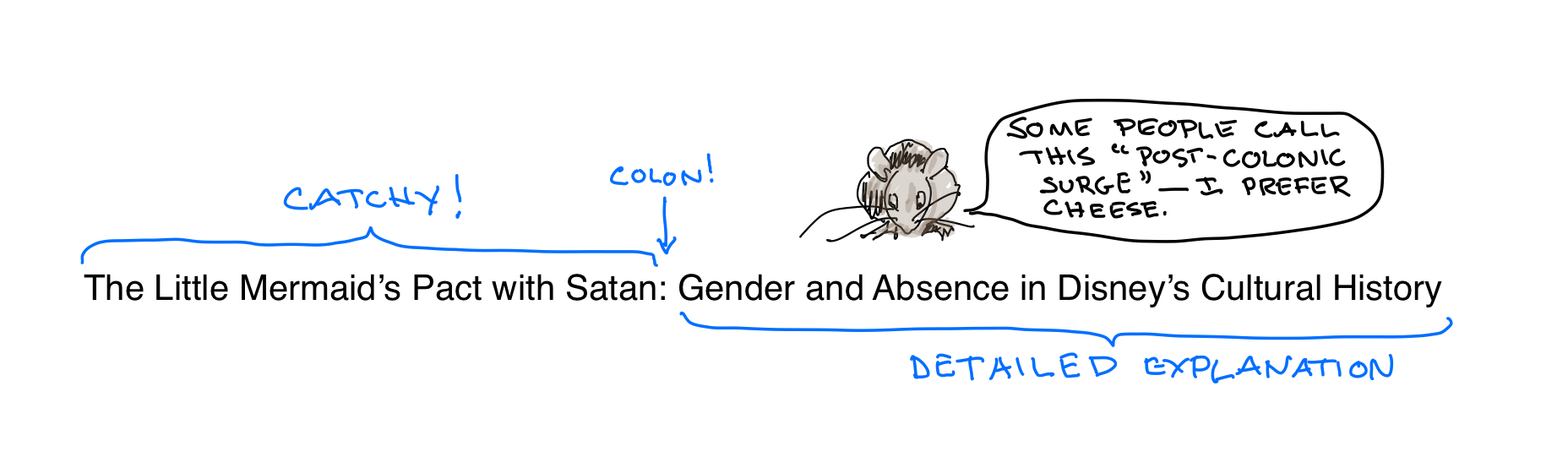

Step 1: A catchy title

Which paper would you rather go hear at a conference? ‘Issues of Heteronormativity and Gender Performance In Twain’s Novels” or “Come Back to the Raft, Huck Honey”?

Your title should be informative and focused, indicating the problem and your general approach. It’s very fashionable in the humanities to have titles featuring a catchy phrase, a colon, and then an explanation of the title. While snappy titles may help your abstract be noticed, it’s really what comes after the colon that sells the abstract, so pay attention to it. “All the World’s a Ship: Race and Ethnicity in Moby Dick” catches the eye, but “Melville’s Deconstruction of Ethnicity in the ‘Midnight, Forecastle’ Episode of Moby Dick” tells readers much more specifically what you’re promising to deliver.

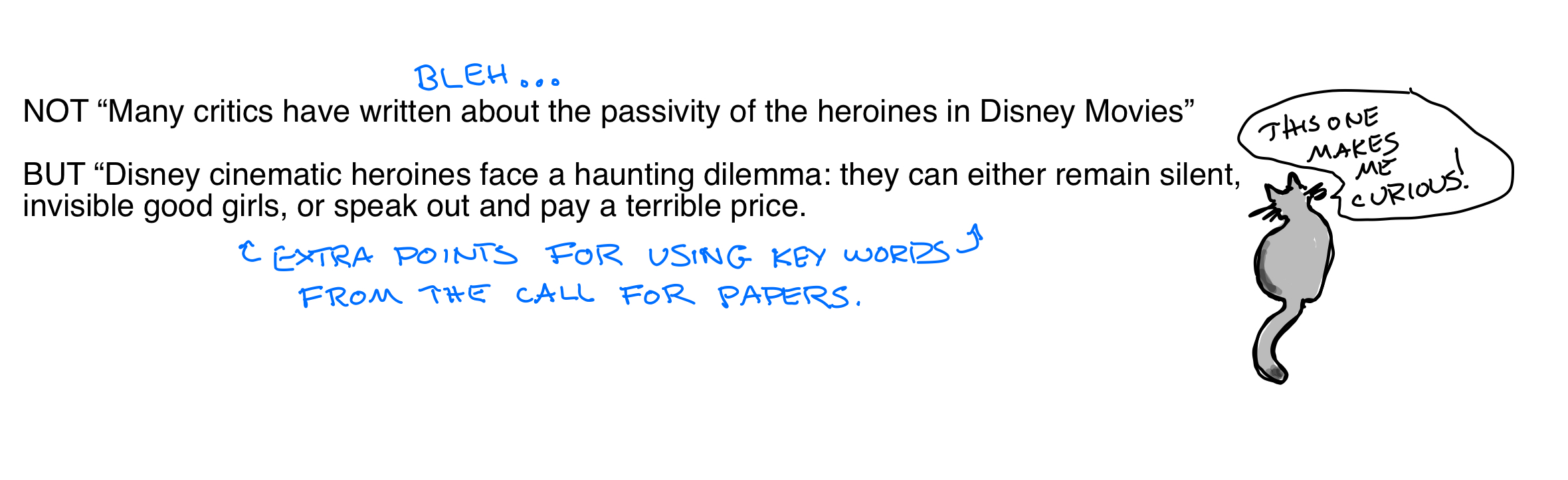

Step 2: A snappy context sentence (or sentences)

The abstract should begin with a clear sense of the research question you have framed. Often writers set this up as a problem: “Although some recent scholars claim to have identified Shakespeare’s lost play Cardenio, that attribution is still not accepted.

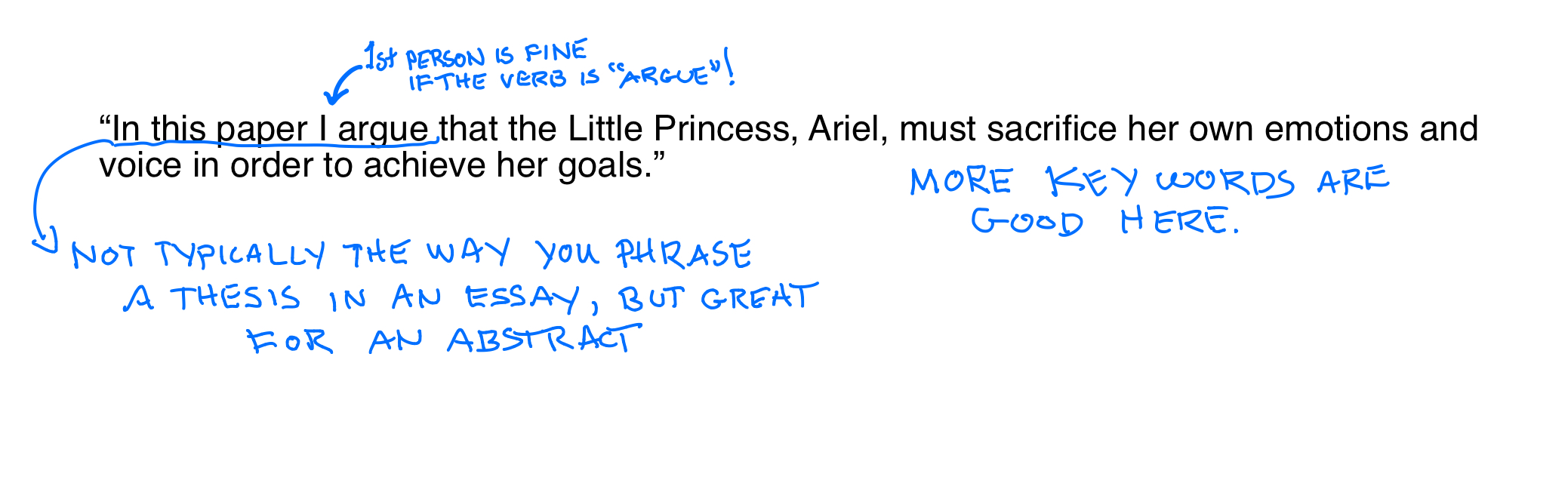

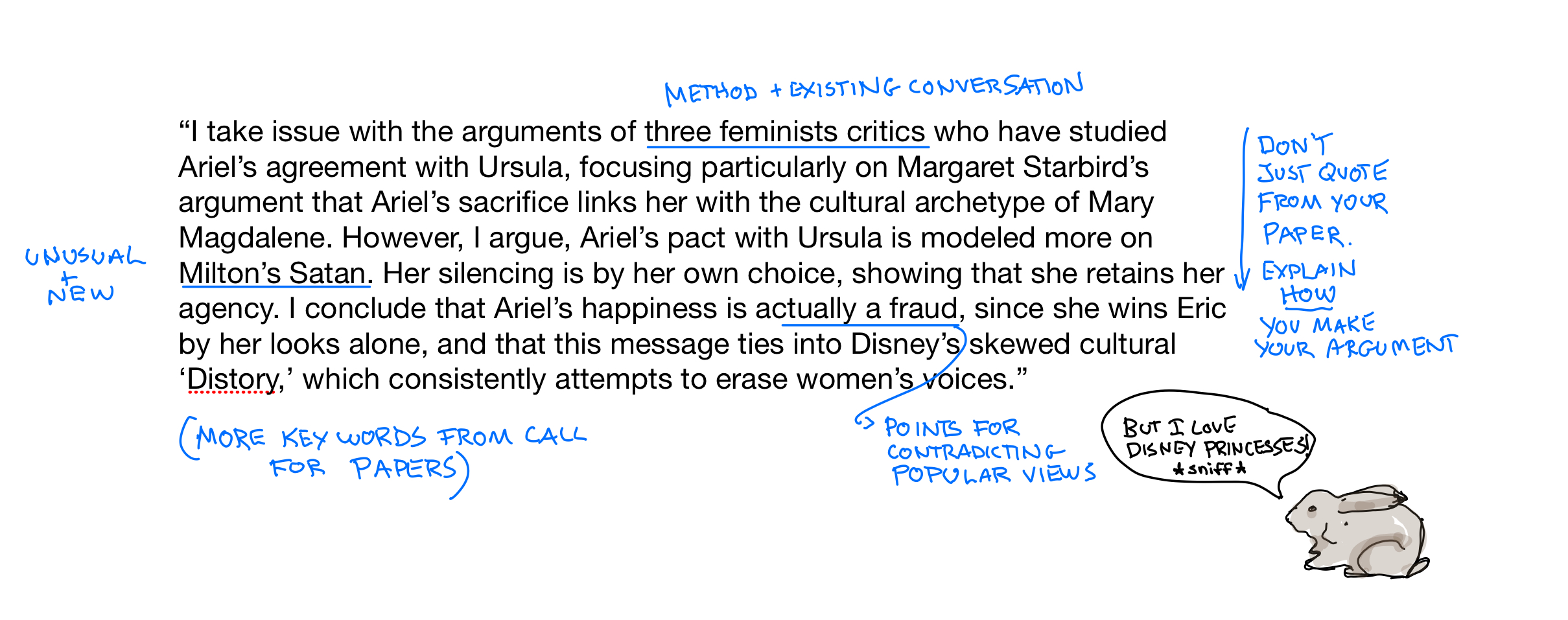

Step 3: Introduce your argument (don’t just copy your thesis statement).

If you began with a problem, you can pose your argument as the solution: “In this paper I use the records of the Worshipful Company of Stationers, London’s chief publishing organization, to show that the play identified by Charles Hamilton in 1990 is not actually the play Shakespeare’s company mounted in 1613.” It’s perfectly legit to use “I” in sentences referring to your argument.

Step 4: Add some sentences describing how you make your argument.

It always helps when you identify the theoretical or methodological school that you are using to approach your question or position yourself within an ongoing debate. This helps readers situate your ideas in the larger conversations of your discipline. For instance, “The debate among Folsom, McGann, and Stallybrass over the notion of database as a genre (PMLA 122.5, Fall 2007) suggests that….” or “Using the definition of dataclouds proposed by Johnson-Eilola (2005), I will argue that…”

Finally, briefly state your conclusion.

“Through analyzing Dickinson’s use of metaphor, I demonstrate that she systematically transformed Watt’s hymnal tropes as a way of asserting her own doctrinal truths. This transformation…”

Not everyone agrees how much jargon should be included in an abstract. My best advice is to add any technical terms you need, but don’t put in jargon for jargon’s sake or just to make it look like you are an expert (this especially extends to (post)modernizing your words or other typographical excrescences).

Special for conference papers:

To the basic requirements of the descriptive abstract, a conference paper abstract should also include a few sentences about how the proposed paper fits in the theme of the conference. For instance, a call for papers for a session on “Science and Literature in the 19th Century” at a conference entitled “(Dis)Junctions” requested “critical works on the interaction between scientific writing and literature in the 19th century. How did scientific discoveries, theories and assumptions (for example, in medicine and psychology, but not limited to these) influence contemporaneous fiction?” If you were submitting a paper to this session, you would want to have a sentence or two about the theories you were discussing and name the particular works where you would identify their influence. If you can work the words “join” or “junction” (or “disjunction”) into your title or abstract, you’ll increase your chance of having the paper accepted, since you’re showing clearly how the paper fits the theme of the session.

Step 5: Show the conference organizers or editors that you’re a pro.

Tell them your essay is a finished work (even if it’s only complete in your head!). It’s also considered good in a conference abstract to conclude with a sentence about your presentation, since the great horror of session chairs is the paper that runs far too long (or embarrassingly too short). Organizers also need to know if you need any special technology to present the paper. So a a much-appreciated professional touch is concluding passage such as, “My paper is complete and can be presented in 20 minutes. I will bring bring video clips on a portable drive but will need a computer, projector, and Internet access to show all my materials.”

Be professional!

Double-check your abstract to make sure it meets the length requirements. Make sure it’s edited and documented. And above all, make sure it’s submitted on time.

Here is a video version of this page, taking you from the call for papers to the finished abstract.

Check out these other guides from CURAH:

- How to write a proposal

- How to make a poster

- A list of regional and national conferences where you can present your work

Acknowledgements:

Illustrated by Ian MacInnes

Thanks to Dr. Leslie Bickford for her sample abstract

I consulted and borrowed material from the following websites in preparing these suggestions:

www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/abstracts.html www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/faculty/bucholtz/sociocultural/abstracttips.html

www.academic-conferences.org/abstract-guidelines.htm

ceca.icom.museum/dbaseupl/writinganabstract.pdf

ling.wisc.edu/macaulay/800.abstracts.html

writingcenter.unlv.edu/writing/abstract.html

www.lightbluetouchpaper.org/2007/03/14/how-not-to-write-an-abstract/

webapp.comcol.umass.edu/msc/absGuidelines.aspx

www.oberlin.edu/history/Honors/prospectus.html

www.english.eku.edu/ma/scholarlythesis.php