As teachers and administrators, we assess our students. We test them to measure their understanding of material. We ask them to write essays to show their ability to construct a scholarly argument. And we have them do research to establish their place in the study of a particular problem. In each case, we provide students with feedback. Some of this is formative: designed to highlight the strengths and weaknesses with the goal of improving performance on the next such assignment. Other feedback is summative, often in the form of grades. The British use the term “assessment” for these activities.

In the United States, however, the term frequently refers to the use of student work for program or course improvement. This should be just as constructive as grading students in a class. But this idea of assessment often seems to carry a negative connotation. Many faculty roll their eyes whenever the topic arises. This is in part because they know that assessment might be used for purposes it was not designed for. Some faculty fear that administrators might use assessment results to reward or terminate faculty. There is a concern that assessment might direct funding or provide talking points in service of some institutional agenda. Just as often and equally damaging, the eye-rolling results from past experience. At times, institutions have collected assessment data without a clear purpose. As a result, stacks of paper moldered in forgotten offices, and electronic files gathered virtual dust on neglected shared drives.

Step One: What Do You Want To Know?

So, to reclaim assessment as a beneficial component of program building, let us examine what assessment can do for you. We will begin with the question that should be at the forefront of any assessment discussion: “What do you want to know?” The answer to this deceptively simple question should lead to a discussion of how best to answer the question. This is the beginning of constructing a worthwhile assessment. One way that assessment differs from just asking questions is that with assessment there is a means to answer the question beyond simple anecdote.

An example of such a process comes from the assessment of the impact of undergraduate research. In a study of the effects of presenting at the Undergraduate Research Conference on students at the University of New Hampshire, the five investigators set out to answer these two questions:

- How do current students perceive the URC impacting their undergraduate experience?

- How do current students perceive their mentors’ role in their academic/research experience?

The investigators sent surveys to each presenter. Using a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions, they collected both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data included student responses using a Likert scale to measure the impact of presenting at the URC on their overall skills and confidence in such aspects as public speaking and taking initiative; they analyzed these responses using statistical methodologies. The qualitative data came from answers to open-ended questions about faculty mentoring and students’ most memorable URC experience. These answers were read and categorized by several individuals and shared themes identified. By coding these themes, the investigators were able to analyze these qualitative data using quantitative methodologies.

Step Two: How Will You Know It?

In constructing a research question, it helps significantly if one conceptualizes a potential way to answer the question as one develops it. These potential ways might include surveys, or evaluation of student-generated artifacts such as capstone work or portfolios of research or creative writing, translation, music performance, and/or artwork.

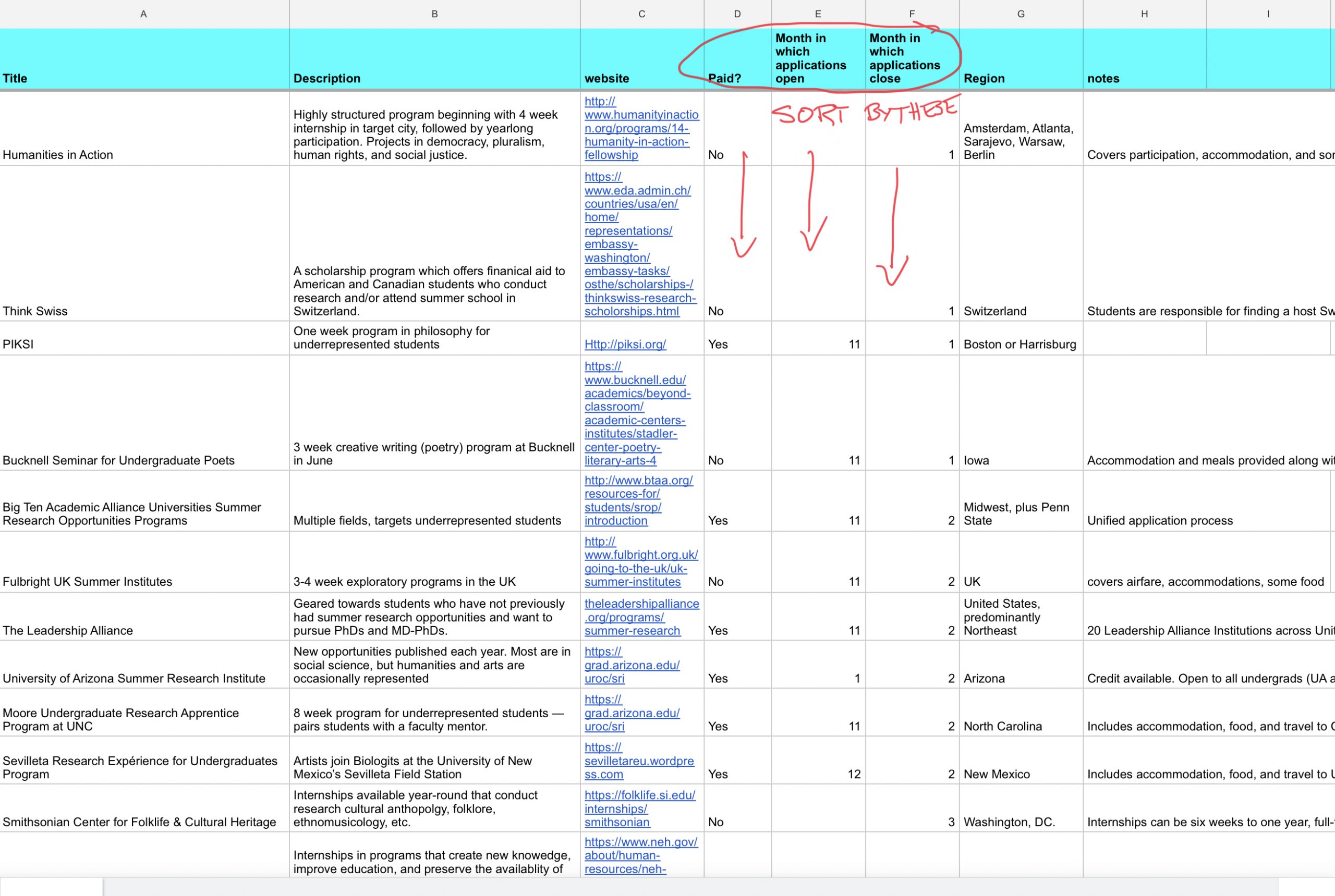

A case in point for the use of student-generated artifacts in program assessment: the first five-year program review of the newly established Art History major at Truman State University, my home institution. We had changed the way we taught a senior thesis in Art History. For example, we moved from one semester with six hours of credit for completion of a thesis, to making the project two semesters, with one three-hour class each semester.

Our major question was whether the theses were showing improvement as a result of the changes, and in what ways. To answer this question, we needed to find measures of quality other than grades. For example, one such improvement could be in the level of ambition in the research. This quality might show up in bibliographies that included both primary and secondary materials, longer and more complete listings of sources, and scholarly articles as well as more general sources. In turn, the improved bibliography might coincide with more sophisticated and more challenging thesis questions. This can lead to more ambitious thesis statements, and hence longer theses.

By gathering data on these two factors, we were able to suggest that the changes we made in the major resulted in improvements. In our study of ten years of data, we found that the length of the average thesis more than doubled immediately after the move from one semester to two. Further, the variety and number of bibliographic sources increased over the ten years under study.

I Need Help! Where Might I Find It?

In the arts and humanities there are several examples and discussions of disciplinary-based assessments and assessment strategies. Here is CURAH’s sampling of some of the resources out there for many of the disciplines collected in the Arts and Humanities Division of CUR, grouped by discipline. Even if one resource is not in your discipline, it is worth looking at what other areas are doing.