By Liam Strong and Julie Gard

Creative writing student Liam Strong and faculty mentor Julie Gard reflect on the challenges and joys of working together remotely at the University of Wisconsin-Superior during the Pandemic.

A Student Perspective – Liam Strong

A Frigid Spring

I had planned on celebrating Pride Month in June 2020 like I would any other year. I’d made a lot of plans, but I’d never accounted for a pandemic. The arrival of COVID-19, however, didn’t halt my one stationary plan of completing my Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) through the University of Wisconsin-Superior.

As a distance learning student, I had already constructed the skeleton of my project online. Working with my mentor and professor, Julie Gard, I planned to write a poetry chapbook manuscript (16-25 pages) by August. Or at least that’s what Julie insisted I do instead of the full-length manuscript I had initially challenged myself with. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the finished chapbook is practically devoid of its influence.

What the pandemic didn’t change was how politically charged the manuscript ended up being. Pride Month wasn’t going to happen once the Black Lives Matters protests began this summer, and they informed the outspoken nature of the manuscript. The pandemic didn’t change the experiments I did with poetic forms, nor with language, nor my hopes for the project.

If anything, isolation brought me closer to myself and my identity, which wasn’t planned at all.

Content, Themes, Meditations

Truth be told, the original title of the project, Like a Body From Blood, was a placeholder. Because the project’s themes began broadly, they weren’t fully realized until almost halfway through the summer. I wanted to write a set of poems about the non-binary experience, about grappling with one’s gender dysphoria. I wanted to celebrate queerness, existing in a sometimes bizarre transgender body and mind, and not be angry.

The poems are sad and indignant (in a mutedly poetic way) because I found myself in everything I had compiled for my Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship project’s reading list. I hadn’t planned on writing poems dealing so much with my body image, with every one of my multitudes. I’m the only one who will say the manuscript is about insecurities.

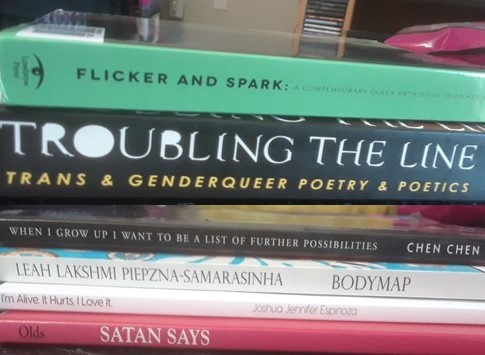

Thematically, what started as my exploration into theorizing non-binary poetics then became a narrative. After reading Bodymap by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, I knew there were roads to my gender fluidity, masculinity, femininity, my physical vulnerability. My emotional vulnerability. Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s I’m Alive. It Hurts. I Love It. reached out to hold me because it knew my pain, my joys, my place in the world. I realized with that book my manuscript needed to do the same.

Workshopping Poems and Myself

I’d often be distracted trying to read the titles of the dozens of poetry books behind Julie’s head while we discussed my poems and readings via Zoom. I’d hear her dog, Nikolai, lawnmowers and endless road construction, or her partner coming home while we workshopped at her outdoor office. I tried, however, not to be distracted by my own expectations toward how I had been writing before the project began.

My weekly poem drafts were unlike any I had written before—largely due to Julie’s feedback and my propulsion to do something different. I was tired of being comfortable, especially with writing the fine-tuned poetic line, and in turn focusing on crafting an evocative, personally charged line. Though not every single poem I wrote took on a specific poetic form, every poem had form in that it was written with purpose in mind. I wrote poems in conversation with the content of my weekly readings; poems in response to another poet’s poem; long narrative poems that were unlike the tight, brief poems I typically wrote.

I could see my body in every poem. Each poem had bones, flesh, genitals, and a name that didn’t fit their visage. The poems were all searching for belonging, and I just didn’t know it yet.

An Audience of One vs. An Audience of Many

Many authors and teachers of writing suggest that one should always write for themselves. At the end of summer 2020, my SURF project implored the opposite. Although most, if not all, the poems in the final manuscript are “about” me, they are not for me.

I titled the chapbook Likeness. Once we had begun composing the list of poems that would make it into the projected order of the manuscript, we realized that the themes extended beyond gender identity and toward kinship, toward finding likeness in others. I wasn’t writing for myself, but rather for people who didn’t have a literature to call their own. Though there isn’t a dedications page, the manuscript is for all transgender, gender-nonconforming, and non-binary individuals. As someone who grew up without any non-binary poetry to see myself in, it became my goal to ensure that others could see themselves in my experiences as a person of gender and sexual diversity.

Certain Uncertainties

Having endured the pandemic thus far, I can’t help but regard the toll it’s taken on my mental health in conjunction with a 200-hour fellowship project. There were days where I didn’t want to look at a poem, then days where all I wanted to indulge in were literature podcasts, poetry collections, and my personal free-writes. There were days where I felt like a boy, days where I was a girl, days where I didn’t want to be clearly defined by a binary. Although many poems over the course of the summer were undoubtedly fun to write (particularly those in response to Chen Chen’s When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities), others became therapeutic. As in, I may not have been ready yet to tackle their emotional baggage.

Bouts of dysphoria would hit me, but during those times the best strategy for coping was gardening. Hours spent picking weeds, trimming bushes, and topping begonias became a necessary reprieve from not only the difficult personal content of my poems but also the social climate of America.

That all said, I won’t discount the newfound relationship I now have with writing and workshopping poems. The workshops Julie and I held weren’t simply devoted to constructive criticism and revision—our workshops were more like discussions of poetic intent, considering how to best fulfill the then uncertain themes of the chapbook. Uncertainty offered so much to me, despite my evasion of it. I may not have found my true self with all these poems, but that was never the point. I will always continually find myself. I have a lifetime of poems ahead of me to write, and this summer of writing has been the bridge between me and the poetics I want to see more of in the world.

A Faculty Perspective – Julie Gard

Writer at Work

Liam’s apartment had white walls, comfortable couches, and a cat. Bookshelves, a washing machine, lamps, and warm light. Outside of the Zoom frame in which much of our mentorship transpired, they described gardening and working in the dirt. I loved to imagine this companion experience to a summer of reading and writing poetry–the tangible digging, planting, and growing. I have never been to Traverse City, Michigan, so their life outside of the apartment was an imaginary space for me. I knew they lived on the third floor, so I pictured them in a fortress up in the air, safe to take on poetic form and the false gender binary.

Set-up and Structure

Liam and I have never met in person; they were a student in my online, advanced poetry workshop in Spring 2020, which is where I got to know their writing and work ethic, sensing they would be a perfect candidate for a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Superior. Our remote mentorship was not a response to the pandemic, but this format certainly turned out to be convenient.

Structure is important whenever a faculty member is accompanying a student on their journey with an independent project, and Liam and I worked together to set up a framework ahead of time, with the understanding that we could tweak it. In the late spring, we developed a timeline that included weekly readings and due dates. We committed to meeting once a week throughout the summer, with these meetings scheduled as “recurring” in Zoom and on both of our Outlook calendars. In between meetings, we agreed to check in over email if any questions or challenges came up.

In terms of our mentorship medium, video meetings have limitations but can be extremely effective as a space in which to discuss creative writing, especially when accompanied by written feedback and exchange. I think of the long tradition of epistolary mentorships between writers, and between writers and editors. In many ways, writing is a well-suited discipline for long-distance work, and adding a face-to-face element, even if virtual, adds another layer of richness.

A Flexible Pedagogy

As a mentor, my role is to help a highly motivated and well-prepared student set up a framework in which they can work independently on a significant project and make discoveries. Providing structure while giving up control is somewhat like teaching a course where the student authors or co-authors the course objectives. In a mentorship of this kind, often the “course objectives” become more focused as the project continues. I now see creative project mentoring as occupying a space between an advanced college writing course and the life-long work of a professional poet. I strive to equip the student with the skills and framework to pursue in-depth creative projects independently in the future.

I know from my own experience with writing mentors such as George Barlow at Grinnell College, and Valerie Miner and Julie Schumacher at the University of Minnesota, that encouragement and praise can very much coexist with questioning, suggesting, and looking deeply into a work. Taking someone’s writing seriously helps them to grow, as does modeling a state of curiosity. This is not a project of dismantling or asserting dominance, but rather of working with a highly engaged student as a collaborator. What is the student curious about? How does this overlap with what I’m curious about? How can a recommendation for revision or further development truly be a suggestion that the student has the freedom to take or leave?

Logistics in Illogical Times

Each weekly meeting began with a general check-in, acknowledging our lives as human beings outside the scope of the project. The social unrest across the country, and in our own cities and states, was often part of the conversation, including how we were responding to and finding ourselves influenced by it. This check-in was followed by a discussion of the week’s reading, and then Liam’s poem drafts for the week and my feedback. Liam provided me with their draft work a couple of days ahead of time so I could prepare feedback, and we could discuss the draft together from an informed place.

At the beginning of the summer, the focus was on individual poems. As the summer progressed, our lens expanded to include, usually at the end of the session, a discussion of the overall manuscript and how it was shaping up. We considered how the poems might interact with each other and themes that were emerging, some expected and some unexpected.

Liam chose the reading list for this project, and it was exciting to read these new-to-me works and become familiar with the growing body of poetry by trans and gender-fluid writers, and to learn about the growing field of trans poetics. As a cisgender, queer person in her forties, I was grateful to have my world expanded in this way. My experience is an illustration of the personal and intellectual growth that is one of the rewards of mentoring.

Web of Connections

Liam completed this project during a time of social and political unrest, in the context of a world-wide pandemic. Both of us acknowledged the stress of these circumstances. Two important coping mechanisms were acknowledgment and integration: making space to discuss how we were impacted by these events, and also allowing them to become part of the summer’s writing.

There were few challenges in terms of the logistics and structure of the internship itself. Technology worked well, and the framework we set up, with some tweaks as the summer went on, also proved effective. Liam completed two versions of a polished, powerful final manuscript. It was deeply rewarding to watch Liam become part of an important literary conversation, sharing their own truth with and among creative peers and kindred spirits.

At our university’s Summer Undergraduate Research Symposium, held virtually in October, I had the opportunity to watch Liam give a powerful reading of several of their project poems. Audience members expressed a heartfelt connection to and admiration for their work. On a personal level, it was rewarding through this mentorship to expand my knowledge of trans poetics, and in turn my own sense of queer community and creative possibility.