Large digital humanities sites can offer great opportunities for undergraduate scholarship. One model project is the University of Victoria based Map of Early Modern London (MoEML), a blend of history, geography, and literary study focused on London in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century. MoEML usually relies on advanced scholars, but through its pedagogical partnership program MoEML also invites mentored undergraduate contributions. It is perfect for contributions from undergraduates who are just beginning true humanities scholarship. And its strong peer review process and insistence on faculty mentoring mean that student contributions are always of high quality. Here two recent undergraduate scholars reflect on their work with MoEML.

Emily Allison, at Albion College, researched early London’s brothels. During the course of a summer project she wrote and encoded the entry for the Cardinal’s Hat in Southwark. Her faculty mentor was Dr. Ian F. MacInnes.

Ashton Davenport, at North Carolina State, researched Stationer’s Hall with fellow students during a recent class with Dr. Maggie Simon.

CURAH:What were the easiest and hardest things about the work you did?

Emily: The easiest thing about the work I did for the Map of Early Modern London was how immediately captivating the research was. I completed my MoEML articles with the help of a summer research grant at Albion College. That meant I was able to treat the project like a full-time job. Even logging 40+ hours a week on my research, I very rarely felt like the process was boring or tedious. Each day I was met with a renewed sense of purpose. I felt like working on the map was a puzzle that I had to assemble before the summer was over.

I found that the most frustrating thing was how my research was never complete. I would think that I had exhausted every source I could find and then stumble across a new one that would bring with it new contradictions and complexities.

Ashton:The easiest part of the project was finding the general research surrounding Stationer’s Hall. It was the location of the governing body for the printing industry in its prime, so hundreds of primary and secondary sources mentioned it. It was also very easy to work with my classmates. We were all in the same major and knew each other. Therefore creating our draft proved easier than I thought it would be. The hardest part of the project was narrowing down our research to only a few sentences. We didn’t want the draft to be too long and tedious. Our group had five pages of research after we were done! We had grown to love every fact we learned about Stationer’s Hall; having to depart from some of those facts and only include the essential ones was heartbreaking.

CURAH:What kinds of things did you learn? (about the early modern period, about scholarship, or about yourself)

Emily: Prior to my work with the Map of Early Modern London, my knowledge of the early modern period was minimal at best. Therefore, before I could delve into the specifics of brothels in early modern London, I had to do a fair amount of research to lay groundwork. Even with this extra layer of research, I found that I could successfully set a schedule for myself and stick to it. That came as a surprise, since up until that point I’d never conducted such an extensive research project. It made me feel like I could handle taking on larger projects in the future. I also learned that independent research can sometimes be lonely and totally overwhelming; I was grateful for the frequent reassurance I received from my advisor that I was taking the proper steps and doing enough, even when it felt like I wasn’t.

Ashton: I had never done research quite like this before, and I learned quickly that there is an abundance of information available regarding anything one wants to research. That’s why narrowing down the research that pertains to your specified subject can be difficult. The filters and advanced search techniques our NC State librarians taught us were helpful. Databases like Early English Books Online (EEBO) were also important. As far as the early modern period itself, I learned about the Great Fire of London, one of the most important events we encountered. The fire burnt down Stationer’s Hall and destroyed most of its important documents. I learned many things about myself, but the most lasting thing I learned was my passion for early modern research. I had always loved it (I have an affinity for King James I), but this project fed my passion. It allowed me to explore some of London’s greatest buildings while also focusing on one small one that had a big impact during my favorite period of history and literature.

CURAH:Did you make any discoveries along the way?

Emily: During my research, I attempted, with increasing difficulty, to find the exact locations of the brothels listed in John Stow’s Survey of London. I came to learn that brothels were often conflated with other public houses (such as taverns and inns), and the more I tried to parse out what brothels were and how they functioned in the early modern landscape, the harder it was to draw clear distinctions between the various types public spaces. This idea of geographical ambiguity formed the basis for my Honors thesis, as I analyzed Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure with the knowledge I had acquired about prostitution in early modern London.

Above all, MoEML helped me understand London’s history—and history in general—in new ways. My research forced me to conceptualize history with geography at the forefront, which was something that I had never done before.

Ashton: My group discovered a source that proved to be everything we needed and more: Cyprian Blagden’s The Stationer’s Company: A History, 1403-1959. This detailed history gave us facts we would use for the majority of our project. Stationer’s Hall moved locations four different times during the early modern period. After the Great Fire of London, the Stationer’s Company set up headquarters in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital for 28 months during the reconstruction of the hall. At the end of the 17th century, the Hall generated revenue from renting out the premises for dances, dinners, and lotteries. This information was the most essential, and it steered our research into the right direction. The discovery of this source was pivotal for our research.

CURAH: How has the project helped you in your career goals?

Emily: My work with MoEML taught me a breadth of new skills that I use at my current place of employment. For instance, part of my job requires that I carefully examine primary source documents to verify historical dates and events. Verification was a major component of my brothel and prostitution research. Conduct ing thorough research and dealing with conflicting ideas also are useful abilities. They help with my work at a state historical society.

MoEML also gave me insight into the nature and intensity of humanities research, which is useful given my plans to attend graduate school in the near future. If I had any doubts about continuing my education, doing research for MoEML solidified not only that I would be able to do it, but also that I might actually be able to do well at it.

Ashton: I am now a high school English teacher in my hometown, and the things I learned from this research project have helped when teaching my students about how to conduct their research. I encourage them to stick with it and not get overwhelmed when presented with the abundance of information, something I had to learn to do myself. My next step is to go to graduate school and achieve a Master’s in English, and surely my research with MoEML will resurface and the tools I used within this project with help me with my further research projects in graduate school.

CUR Councilor Ian F. MacInnes is MoEML’s U.S. Agent for Pedagogical Partnerships. If you have an interested student or are thinking of working with MoEML in the classroom, please contact him.

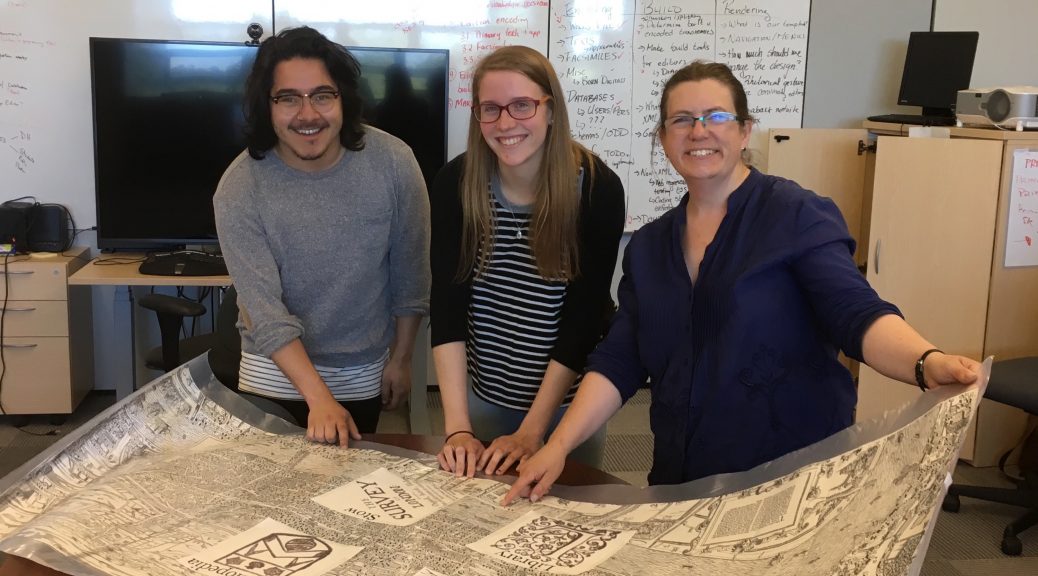

cover photo: Programmer Joey Takeda, Student Emily Allison, and MoEML Director Janelle Jenstad with a replica of the Agas Map of London in the University of Victoria offices of MoEML

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License